They are counting on our health

Many health-related decisions are based on biostatistics. Meet three researchers who make the calculations that could affect your life.

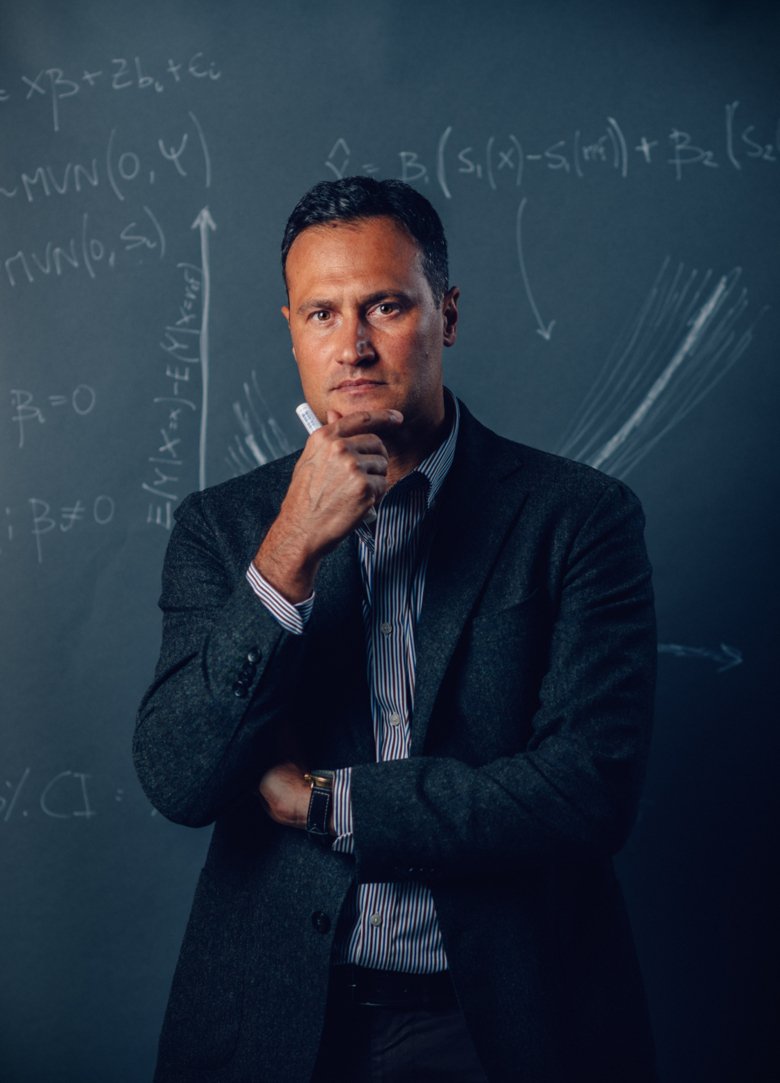

"You imagine what could happen"

Name: Nicola Orsini

Title: Researcher at the Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet.

Conducts research into: Development of biostatistical methods.

“The best thing about biostatistics is that you imagine what could happen; a breakdown of the findings is already predicted before any data is collected. Biostatistics includes planning what to measure and how – as well as analysing and interpreting outcomes. And since many health-related decisions are based on statistics, there is a growing need today to better understand and evaluate the conclusions that are drawn from all the data. Statistics can help us see a pattern behind seemingly confused observations. It takes care of uncertainty about real phenomena.

My main interest is research into what are known as synthesis methods, especially meta-analyses – when smaller studies are merged into one large one – of dose response. The results of these meta-analyses can often have a major impact on health researchers and policy makers. International health organisations, which provide information on factors believed to affect health, often rely on these results. For example, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) analyses how cancer prevention and survival are related to diet, nutrition and physical activity. I collaborate with researchers from different disciplines and have the opportunity to develop statistical methods that in the long term change the way research is done.

Some students may find biostatistics difficult. Others may find it easy because they know how to use software for statistical analysis. The impression that students get depends to a large extent on how the subject is taught. Teaching can make the difference here.”

"I'm trying to predict the future"

Name: Martin Eklund

Title: Researcher in epidemiology at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet.

Conducts research into: AI systems and predictive models with the aim of improving cancer diagnosis and treatment.

“Who should have a biopsy? How should it be done? It is important to always choose the right action for the right patient. Through predictive models and machine learning, we can improve cancer diagnostics and treatment.

I try to predict the future of men with suspected or diagnosed prostate cancer. Diagnostics is very much about decision-making. Today, there is a risk that pathologists assess tissue samples differently, which increases the risk of over and under diagnosing. My colleagues and I have shown that it is possible to develop AI systems that have as high a degree of accuracy as the world's best uropathologists. In future, I believe that people and AI systems will work even more hand-in-hand so that more people with prostate cancer can get adequate treatment.

Our predictive model for more accurately choosing which men to biopsy is now clinically implemented. That is really good.

The most enjoyable part of my research otherwise is the creative process, thinking about new research projects – sometimes spontaneously during a coffee break, other times in a more planned way in meetings. What drives me is that it ends up in something that helps people at the end of the day.

Biostatisticians are needed throughout the research process. We are used to thinking about pitfalls, both when planning a study and when analysing data later. To be able to be a biostatistician, I think you have to have a combination of curiosity, creativity and accuracy. My best work tool is of course the computer with statistical software for making calculations.”

"I often use pen and paper"

Name: Therese Andersson

Title: Researcher in the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet.

Conducts research into: Statistical methods for measuring cancer patient survival.

“Many people may think that we biostatisticians only make calculations for researchers, but we are researchers ourselves. I mainly focus on cancer epidemiology and survival analysis and collaborate with many different researchers, clinicians and epidemiologists. It is so interesting to constantly learn so much about different forms of cancer. All my method development is rooted in questions that the people I collaborate with are working on. I tend to see if their questions could be better answered if we developed a different statistical method.

Neither friends nor family understand what I do, but if I'm going to try to explain it, I usually talk about five-year survival, which is a standard measure of cancer survival and something most people have heard of. I tend to say that this is a good measure, but that it does not answer everything. That is why I'm working on developing other ways to quantify survival, such as the number of person-years lost by the cancer sufferer or life expectancy compared to the general population.

I also develop complex models to get a better picture of what happens during the progression of the disease in various cancers. Today we have more and more information and can therefore analyse data in a better way than we could before. But this also places higher demands on the methods we use and it is important that these continue to develop.

The most important work tool is my computer with a special computer programme for statistics. But I often use pen and paper when I sit and think about how to perform different calculations.”

As told to: Maja Lundbäck, first published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 4/2020.

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesBiostatistics at KI

Researchers in the field of biostatistics study the theory, tools, and applications of methods for the collection, analysis, presentation, and interpretation of biomedical data. They work closely with experts in various other academic fields in order to advance scientific knowledge.

Photo: Rickard Kilström

Photo: Rickard KilströmHelping medical scientists analyse causal relationships

Arvid Sjölander works with statistical tools and mathematical models to help medical scientists make more reliable estimations of causal effects. Meet one of the new professors of Karolinska Institutet.