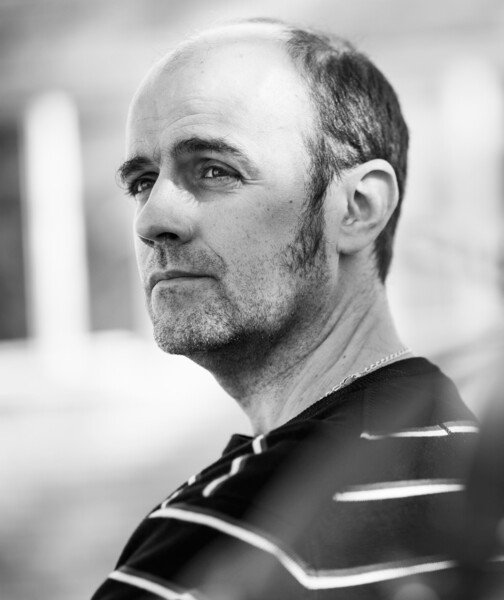

Óscar Fernández-Capetillo chases unanswered questions

Happy people work better, according to Óscar Fernández-Capetillo, who argues that research should be enjoyable. In addition, he hopes to help patients with both cancer and ALS. Meet the Professor who avoids falling in love with his projects – but adores research.

Name: Óscar Fernández-Capetillo

Title: Professor at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet. Also leads a research group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain.

Age: 41

Family: Wife Matilde who is also a researcher, three sons and a daughter.*

Motto: A man will never be able to live without his own approval (Mark Twain).

Role model: I don’t have idols. I appreciate values like generosity or humour more than success.

Relaxes by: I very rarely do. But during the summer I occasionally go fishing in a canoe on my own without a telephone –that's true relaxation. I also like picking mushrooms with the kids.

Most unexpected research finding: That the speed at which you age is affected early on during foetal development.

Text: Cecilia Odlind, first published in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 2, 2016.

THE SEARCH FOR UNANSWERED questions is what drives Óscar Fernández-Capetillo's work.

“My research does not have one particular objective. I dedicate my life to science as it gives me the unique opportunity to help and continuously develop whilst having fun at the same time,” he says.

Shortly before applying to University, two people close to him developed cancer and died. He therefore decided to study biomedicine. When he was given the chance, he specialised in cancer.

“The experience awakened a sense of duty in me to take part in the war on cancer. Even though my loved ones were forever lost, they are a source of motivation to do good and to succeed. And to actually enjoy life while I am alive,” he says.

Óscar Fernández-Capetillo's research came to focus on how DNA damage causes ageing and cancer. When a cell divides into two, its genetic material is copied. This is a complicated process as the cell's DNA, which is three meters long if stretched out, must be packed up, doubled and then saved.

“Our DNA must do quite a bit of gymnastics to accomplish this,” he says.

It doesn't always work smoothly either; a phenomenon known as replication stress. At present, we know that the DNA damage which regularly occurs when cells duplicate their genomes can explain the genetic rearrangements that causes cancer. To protect us against replication stress, all cells have an enzyme called ATR. Cancer cells, which split many times in a short space of time and therefore have high loads of replication stress, particularly need this enzyme to survive.

“ATR can be compared to a fireman who puts out fires when one occurs. If you prevent a fireman from putting out a fire when it is fully ablaze, inhibiting ATR in cancer cells with high levels of replication stressthis has a significant effect. The cancer will burn up. This is the reasoning we used when we developed a molecule that hinders the ATR and used it to kill tumour cells,” says Óscar Fernández-Capetillo.

AND IT WORKED. Based on the molecule which they had identified, they developed a drug which was able to stop tumor growth in mice. The medicine has now been sold to the pharmaceutical company Merck, which will test it in clinical trials with humans. Since then, the research group has also identified two types of tumours where the medication may potentially have an especially positive effect. They have also tried to predict potential mechanisms of resistance to this treatment, i.e., mutations in the DNA of the tumor cells which may render the medication ineffective.

“We don't know if these mutations will occur in the clinic, but we have identified a drug which we can use to treat the resistant tumors if they do. We also have found a biomarker that can be used to identify which individuals are more likely to respond to the treatment. This will hopefully be helpful when testing the medication on humans,” he says.

Óscar Fernández-Capetillo also believes that replication stress can explain the ageing process. In previous studies using prematurely aged mice, his research group has seen that mice who produce additional amounts of nucleotides, the building blocks of DNA, had lower amounts of replication stress and aged more slowly.

“Elderly people have long been given vitamin B, folic acid, to treat a number of ailments. It helps to prevent cataracts and hearing loss, for instance, but we do not know why. We think that part of the explanation could be that folic acid, which is used to produce the building blocks of DNA, reduces the risk of replication stress,” he says.

IN HIS QUEST TO discover new areas, Óscar Fernández-Capetillo also allows himself to dedicate his time to other projects, with less clear goals. One of his latest projects is to try to create a haploid mouse, i.e., an organism that has only one set of chromosomes, as opposed to two (one from the mother and one from the father).

“Why are we doing this? Because it hasn't been done before!”

But he also sees the potential benefits of the project. If they succeed, this can become a technology that facilitates the study of genes' functions in vivo. If we eliminate a certain gene, then there is no compensatory gene from the other parent which can step in to replace the damaged gene.

“It's difficult, we don't know how to do it yet, but I am also sure it’s possible.”

Óscar Fernández-Capetillo does not believe in focusing too much on what may or may not work in beforehand. On the contrary. As an illustration, he tells the story of what happened when the cancer drug Cisplatin was discovered. The researcher wanted to examine whether electricity could kill living cells. The first experiment seemed to demonstrate that it could. But the results could not be replicated. The researcher then realised that the only difference between the two experiments was the material surrounding the electrical cable. The cells could not grow around the cable that was covered with platinum. This is how it was discovered that this substance was cytotoxic.

“Was it a good experiment? I don't know. But if it had never been done, we wouldn't know what we know today,” he says.

ÓSCAR FERNÁNDEZ-CAPETILLO prefers to think positively.

“Now and again, I meet with egocentric persons who only ask 'Why DID you do that?', just to highlight their own excellence. But I would rather surround myself with people who ask Why DON’T you do that,” says Óscar Fernández-Capetillo.

He views life as a series of random events.

“Ten years ago I would never have dreamed that I would be conducting the research that I am at present. Likewise, I hope that in ten years I will be conducting research on subjects that I currently can't even imagine,” he says.

With this mindset, events around the world in recent years have inspired Óscar Fernández-Capetillo to take an interest in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, a fatal and incurable muscle disease that affects one to two per 100,000 people each year.

“When the ALS 'ice bucket challenge'* was all the rage, I started reading about the disease and discovered, to my surprise, that the molecular principles of this disease were to some extent related to my own work. That gave me a whole load of new ideas,” he explains.

CURRENT MEDICATION ONLY modestly works for some patients and does not significantly extend survival. His group is looking for alternatives. The goal is to stop the death of nerve cells that control the body's muscle movements, which ALS patients suffer from.

“I don’t know whether we will succeed in bringing new medicines to ALS, but we will certainly try” he says.

In 2014, Óscar Fernández-Capetillo was listed on the reputable journal Cell's “40 under 40” list, with the 40 most prominent researchers under the age of 40. But being on lists or being published in important journals is not a goal in itself for Óscar Fernández-Capetillo.

“Some of my older colleagues are still really thrilled if one of their articles is published in one of the more prestigious journals. But that doesn't do it for me; getting a paper published only brings me relief as it allows me to stop doing beautification experiments for reviewers, and focus on discovering new things.”

Different researchers clearly have different incentives. And in an ecosystem as large as the world of research, there is room for all sorts, according to Óscar Fernández-Capetillo.

“The scientific arena is a big pool. There are sharks and beautiful, red balloon fish. I consider myself as a small curious fish, who likes to amuse himself by teasing the big sharks when I am bored,” he said.

Isn't that dangerous?

“So far I always got away in one piece!”

* The ice bucket challenge started in 2014 to raise money for ALS research. Films spread all over social media of people voluntarily pouring ice cold water over themselves in sympathy with sufferers.

Óscar Fernández- Capetillo on…

…being wrong

“I am often wrong which is okay. The difference between a good and a bad researcher is that a bad researcher does not use a trash-can when needed. Being dogmatic is dangerous; we are most often wrong.”

…research fraud:

“There are people that cheat at all levels, regardless of the impact factor. However, articles that are published in the most prestigious journals are scrutinized much more carefully, which is why it is more often spotted in these journals.”

...moving on

“Good researchers abandon a project and change direction when the first idea doesn't work. This often happens; I have not had a single PhD student who has had the same project throughout their studies. They all started at one end and finished at another.”

...writing scientific reports

“It's incredibly boring. Once I've found out how something works, I want to explore new ideas. In contrast, I enjoy having discussions with others – that always inspires new, stimulating ideas.”