What is Internationalisation of the Curriculum (IoC)?

Internationalisation of the Curriculum (IoC) has become a fundamental factor in Higher Education where best practices aim to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education. The implementation of IoC is raising awareness around the formal curriculum design and informal 'hidden' curriculum, content, pedagogy, learning activities and assessment.

[Internationalisation of the Curriculum] is the incorporation of international, intercultural and/or global dimensions into the content of the curriculum, as well as the learning outcomes, assessment tasks, teaching methods, and support services of a program of study

Curriculum development is therefore the process of integrating specific areas of educational competence into the content of the curriculum, its outcomes and teaching and learning arrangements, as well as the support services of a programme of study, with a view to promote quality learning:

- As a process, curriculum integration is an important part of the periodic, critical review of the curriculum.

- It should include reflection on the impact and outcomes of teaching and assessment practices on student learning and a review of content and pedagogy.

- In this process it is important to recognise past and current successes (and making them visible), as well as imagining new possibilities and striving to improve the curriculum.

Please note that many tools presented to you here are adapted from Prof Betty Leask’s IoC project to suit the Swedish context, and more specifically the context of Karolinska Institutet.

The curriculum

It is important to note what is meant by curriculum. It is a student’s journey at a higher education institution through:

The formal curriculum: the courses, training, assessment and learning activities students participate in, as well as the knowledge and skills intentionally taught to students (intra-curricular) This is the curriculum that is documented in course syllabi and descriptions;

The informal curriculum: the learning experiences from other agencies outside the formal setting, such as student-led initiatives, student support services, social and educational activities, etc. They are extra-curricular;

The hidden curriculum: the processes, pressures and constraints that fall outside the formal and informal curricula, and which are often unarticulated and unexplored. They are the unspoken or implicit academic, social, and cultural messages that are communicated to students.

The curriculum thus has direct implications for the stakeholders of IoC within an institution. The success of implementing IoC at KI was dependent on identifying the correct stakeholders to involve and to provide support to them, through the Unit of Teaching and Learning at KI. The stakeholders comprised:

- Those responsible for the content, intended learning outcomes, assessment tasks, and teaching methods of the curriculum;

- Those responsible for the delivery of support services to the students of a study programme;

- Students.

The IoC framework

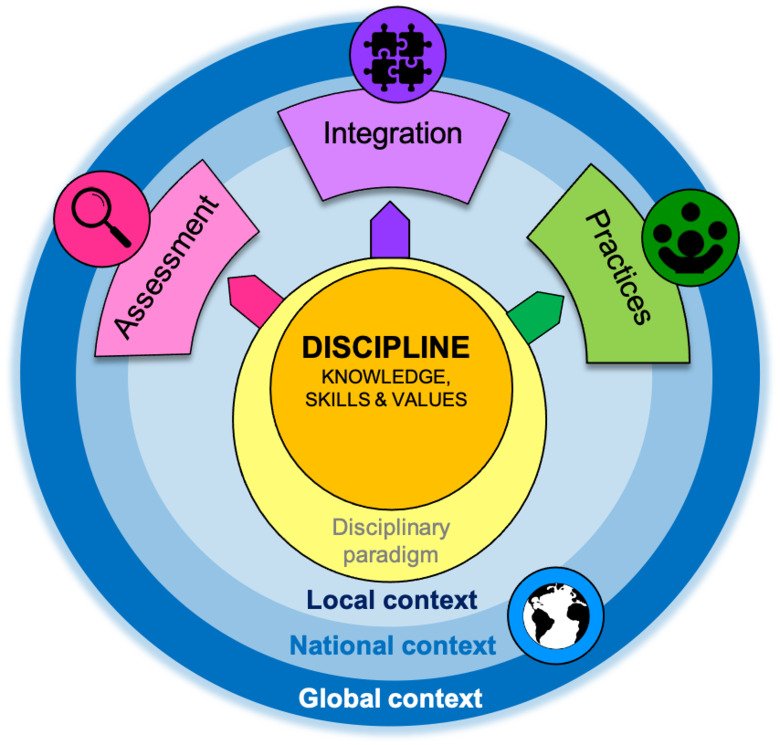

We have adapted the conceptual framework to our context from Leask (2015:27). It places the discipline (and the people who contribute to the curriculum) at the centre of the internationalisation process.

IoC thus means different things in different disciplines because the international perspectives required by different professions vary (Leask, 2011: 13). In short, it is the discipline that shapes the requirements of what makes up the curriculum. The framework below shows the complex relations and interactions of the discipline with the “supercomplex” (Barnett, 2000: 257) and the “superdiverse” (Bloomaert & Rampton, 2011: 2) world in which we live.

Assessment: The systematic development and assessment of linguistic competence, intercultural competence, international disciplinary knowledge and global engagement;

Integration: The integration of skills, values and attitudes across a programme of study at varying degrees of difficulty;

Practises: The global, international, intercultural and linguistic requirements of (professional) practice and citizenship.

Together, these elements are embedded in dominant disciplinary paradigms. Disciplinary paradigms are a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitutes legitimate contributions to a specific field. They reflect ways of thinking, ways of seeing and ways of doing inherent to a discipline at a particular institution. This means that curricula are not neutral; on the contrary, they deeply influence the attitudes, values and behaviours of our learners.

It is vital for future healthcare professionals to consider and understand their patients’ different perspectives, as well as reflect on and be critical of their own normative frameworks of (healthcare) understanding. An important principle to apply is “think global, teach local” (Knipper et al., 2010), where students are encouraged to learn about issues related to migration and health at global levels (e.g.: epidemiology, legal frameworks and intercultural cooperation), at national levels (e.g.: the history of migration and immigration policy in Sweden), and at local levels (e.g.: diversity of the local population in Stockholm).

...think global, teach local

The contexts: The different contexts represented in the bottom half of the IoC framework above regard the different contexts in which the disciplines are enacted. But they also refer to the different levels of governance that affect internationalisation in Sweden. These combined documents provide either rules to abide by or recommendations and guidelines to follow, and provide educational developers with a useful roadmap for the integration of global, intercultural, international and language perspectives in the curriculum.

The local level

Everyone has healthcare requirements that need to be met by the local healthcare system. The concept of superdiversity presents a new opportunity for understanding access to healthcare in Sweden.

According to Sweden Statistics, we know that roughly 40% of Swedish nationals living in the Stockholm region have either one or two parents born abroad or were born abroad themselves. This superdiversity transcends previous theories of multiculturalism in that it recognises a level of social, cultural, economic and legal complexity defined by the dynamic interplay of overlapping variables including country of origin (comprising a variety of possible variations such as ethnicity, language, religious tradition, regional and local identities etc.), migration experience (often strongly related to gender, age, education, socio-economic status) and legal status (implying a wide variety of entitlements and restrictions). Our healthcare systems and our teaching paradigms must therefore incorporate how to navigate this superdiversity (Bradby et al., 2019).

International perspectives in Karolinska Institutet (KI) Strategy 2030

KI Strategy 2030 explicitly addressed these concerns: international perspectives feature prominently, and it is recommended they are incorporated through a process of integrated internationalisation (Bladh et al., 2018: 3). The strategy also recommends that all programmes prepare their students for global citizenship, through such efforts as Internationalisation at Home (IaH) and through the inclusion of global health perspectives in the curriculum.

The national level

The Higher Education Act (Högskolelagen) and the Higher Education Ordinance (högskoleförordningen) list intended learning outcomes for all first- and second-cycle degree programmes and also for specific study programme, but also specifically for the internationalisation of education.

The Swedish Strategic Agenda for the Internationalisation of Higher Education and Research sets out objectives for all Swedish higher education institutions to follow, and more specifically objectives in 3 and 6 focuses on the curriculum ant its impact: “All students who earn university degrees have developed their international understanding or intercultural competence” and “Higher education institutions have strong potential to contribute to global development and global social challenges” (Bladh et al., 2018: 17).

The global level

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a useful framework to work towards. Two SDGs in particular provide useful learning outcomes for KI: SDG 3 on good health and well-being, and SDG 4 on quality education.

Sustainable development goal 4.7

Target 4.7 directly states that education must “ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development”.

The indicator that will ensure that target 4.7 has been accomplished is the following: “Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development, including gender equality and human rights, are mainstreamed at all levels in: (a) national education policies, (b) curricula, (c) teacher education, and (d) student assessment.

SDG4 overlaps to a large extent with the aims of IoC, specifically the emphasis of valuing cultural diversity, equality and equity, a sense of personal responsibility and active self-reflection on one’s own perspective and position in the world. As such, implementing IoC, may be one way of implementing parts of SDG4.7 and therefore ensuring quality education in an era of sustainable development.

The IoC process

The IoC process unfolds over 5 stages addressed by curriculum development teams within each study programme, they are represented in Figure 2. The entire process is lead and facilitated by a team of educational developers. Each stage is accompanied by a focus question:

- Review and reflect

To what extent is our curriculum already internationalised? - Imagine

What other ways of thinking and doing are possible? - Revise and plan

Given the possibilities for IoC, what changes do we want to make to the curriculum, to courses, to support services? - Act

What actions do we need to prioritise in order to reach our internationalisation goals? - Evaluate

How will we know if we have achieved our internationalisation goals and to what extent?

References

Barnett, R. (2000). Realising the University in an Age of Supercomplexity. Ballmoor, Bucks: The Society for Higher Education and Oxford University Press.

Bladh, A., M. Wilenius, and A. Gaunt. (2018). Internationalisation of Swedish Higher Education and Research–A Strategic Agenda. Stockholm: Swedish Government Official Reports. Accessed 15 March 2019

Bloomaert, J. & B. Rampton. (2011). “Language and Superdiversity”. Diversities, 13 (2).

Bradby, H., K. Krause, G. Green and C. Davison. (2019). "Superdiversity and Navigating Healthcare Pathways”. Uppsala: Uppsala University, accessed 24 April 2019,

Knipper, M., S. Akinci, and N. Soydan. (2010). “Culture and Healthcare in Medical Education: Migrants’ health and beyond”, GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung, 27(3), 1-6.

Leask, B. (2011). “Assessment, Learning, Teaching, and Internationalization: Engaging for the Future”, Assessment, Teaching, and Learning Journal, 11: 5-20.

Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the Curriculum. New York and London: Routledge.