Rationale behind Internationalisation of the Curriculum (IoC) and who to involve?

Many universities, including KI, feature internationalisation as an integral part of strategic planning initiatives with economic, political and social changes driving an increasingly global knowledge economy. There are many courses and teaching activities throughout our campuses that address global, international, intercultural, and language perspective in our curricula.

Engaging in an IoC process will allow programmes and disciplines to:

- Move beyond isolated, optional subjects, experiences and activities;

- Develop planned and systematic processes backed by scholarship of teaching and learning.

Yet, IoC serves not only as a tool for programmes and those directly engaged in their development, but also for actors such as educational developers. It provides them with the opportunity to apply research-based evidence in order to move beyond an understanding of internationalisation as an ad hoc initiative concerned with international student and staff exchanges, to one that intentionally “enhance[s] the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society” (De wit et al., 2015).

Embedding internationalisation

Internationalisation initiatives are more likely to success if they are embedded through the transformation of institutional language, culture(s) and attitudes into standard university practice, rather than seen as being developed in parallel, and somewhat outside of, regular university operations. KI is now faced with the challenge of developing a sustainable and integrated, rather than a one-dimensional, approach to internationalisation.

Six key questions

IoC will be the method used to instigate a paradigm shift of KI’s conception of education and integrating internationalisation into regular operations. More specifically, six questions will be addressed:

- How can we internationalise the curriculum in a specific disciplinary area in a particular institutional context and ensure that, as a result, we improve the teaching and intended learning outcomes for all?

- How can we move beyond isolated, optional subjects, experiences, and activities haphazardly spread across the curriculum, to a planned and systematic process that focuses on all students?

- How do we engage academic staff (and leadership) in the process of IoC?

- How do we implement international/intercultural/global/language intended learning outcomes in the content, teaching and learning activities, and assessment tasks in our educational programmes?

- How do we monitor and follow-up the IoC process efficiently?

- What tools, training, incentives and support strategies are needed for effective IoC?

The stakeholders

One important part of the process took the team much time, it was identifying the stakeholders and beneficiaries of IoC – this is why it is key to include persons with knowledge of how your institution is structured and how it functions.

It is essential that the right people be selected since they will implement the findings of the IoC project. This group will debate issues, negotiate meaning, and develop shared understanding of what IoC means for their discipline and their context. They also need to be able to make decisions about the content, teaching and learning activities, and assessment in their programmes. It must be stressed that it took the project group significant time to select and understand who to involve as primary beneficiaries, secondary and tertiary stakeholders.

A three-tier model

Since IoC features substantial interdependencies among multiple systems and actors within a university, developing and implementing innovative solutions involve the re-negotiating of settled silos. This is why we introduced a three-tier model highlighting the different strata of institutional activity (illustrated by the figure below). The model conceptualizes micro, meso and macro levels of institutional responsibility across our three target actors, students, teachers and administrators:

The micro level

- Engaging with students in a way that they can comment on and contribute to the development of an internationalised curriculum, providing them with tools and support in developing language competence, and intercultural competence;

- Supporting teachers and course leaders in rethinking the content and delivery of their courses, providing them with tools and professional development in the areas of language competence, intercultural competence, international disciplinary learning and global engagement;

- Getting support staff involved by offering professional development in intercultural competence.

The meso level

- Student unions and student representatives;

- Programme leaders and committees, including any person(s) responsible for educational development (GUA) as well as person(s) responsible for internationalisation at the programme level;

- The different instances of support services for teaching and learning, ranging from Academic Writing Support, to KI Library and Student Health.

The macro level

The macro level consists of decision-making bodies within the university to ensure the work carried out is anchored and supported in order to ensure motivation and engagement of all stakeholders, these included:

- the Committee for Higher Education

- the Working Group for Internationalisation

- the Unit for Teaching and Learning

- Education and Research Support.

The study programmes

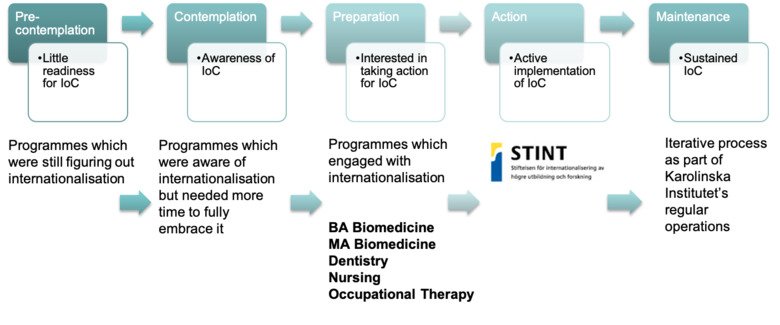

In order to identify the readiness of 5 study programmes for embarking on the IoC process, we used a stages of change model prominent within health care promotion (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

References

Prochaska, J. & DiClemente, C. (1983) Stages and processes of self-change in smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 5, 390–395.