Curious about eating habits

Through our eating habits, we can influence both our own health and the health of the planet. More plant-based food and less meat would be beneficial for our well-being and the environment according to most researchers. But can we acquire a taste for just about anything?

Text: Maja Lundbäck. First published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 4 2020

The scent of cinnamon sweeping past our nostrils can really make our mouth water. Many of us associate this spice with buns and pastries and thus also sugar. Sugar equals carbohydrates, which give us energy. Perceiving a sweet taste in the mouth as something good is genetically determined. In the same way, bitter tastes are perceived as bad, which is not so silly, because bitter flavours can mean poison, which is dangerous for us. Studies of newborns show that we have an innate predilection for certain tastes.

“Right after birth, we see that babies are happy with sugar, but not with bitter tastes,” says Janina Seubert, researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet.

Today she is studying how we can try to change our eating habits – whether the aim is to become healthier or more climate friendly. She believes that we can all learn to love healthy and sustainable food – and that the way to get there is through the nose.

“When we put food in our mouth, we taste it with the tongue while olfactory molecules go up to the nose. Both smell and taste contribute to what we like and don't like, but I think it's important to distinguish smell from taste,” she says.

Unlike tastes, we have not found that there are any smells that we were born to like or dislike.

“Instead, we believe that the smells we prefer are due to associative learning. We have seen in our studies that smells have a taste association,” says Janina Seubert.

Smell the food or drink

Provided we are not sitting in a pitch-black room and have a cold, we have time to both look at and smell the food or drink before we put it in our mouths.

"Beer is bitter and usually not liked by children, but as an adult you might start consuming more and more beer, often in happy contexts – and after a while you start to like the bitterness in the beer.

Many adults who get to look at and smell a beer probably think that it will be good to drink.”

This is good news for people who wished they ate more vegetables, but who perhaps mostly like prefer sausages. It is not so easy to just replace food that we really prefer with other types of food straight off, but there seems to be room to relearn and to grind away our preferences for unhealthy and unsustainable food.

Liselotte Schäfer Elinder is adjunct professor in public health sciences at the Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet. For many years she has been studying how we can improve our health through changes in our eating habits. An unhealthy diet, together with physical inactivity, tobacco and alcohol, is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Today Liselotte Schäfer Elinder is also interested in how we can influence the climate in the right direction by changing our diet.

“Climate-smart and healthy eating habits often go hand in hand. One exception is sugar, which is climate smart, but unhealthy,” she says.

Eat more plant-based foods

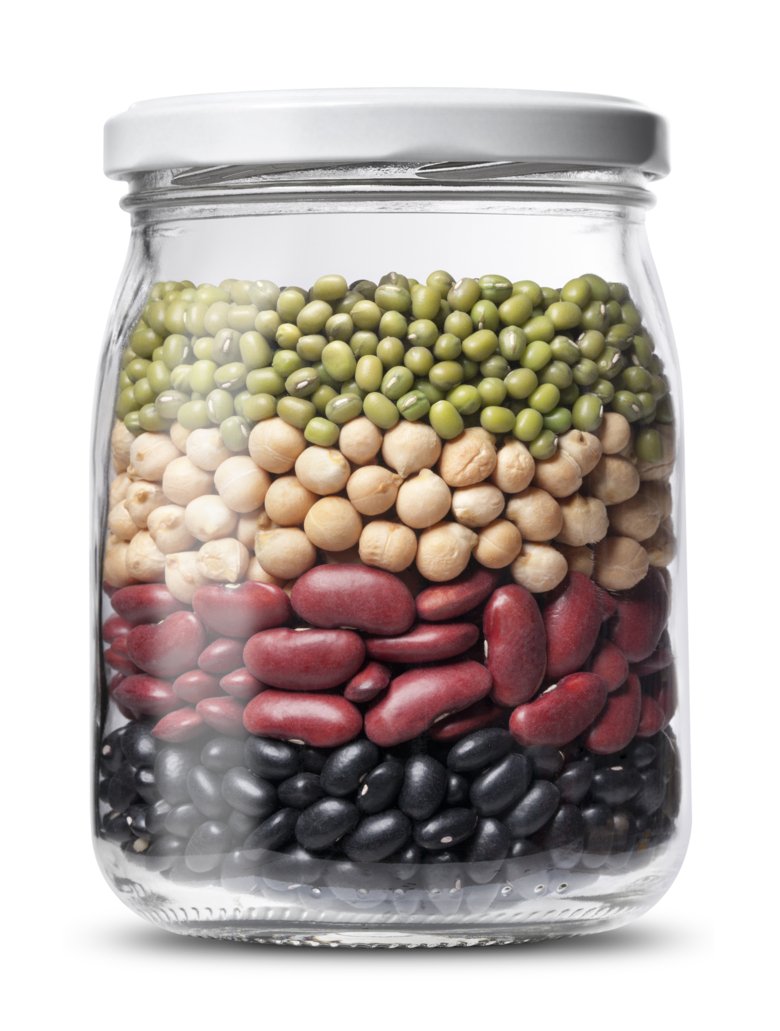

Most scientists agree that we need to eat more plant-based foods and reduce our intake of animal foods, especially red meat and processed meat products.

“Food production and consumption accounts for 25 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions need to be at least halved. Today, there are estimates of what such a diet might look like to benefit both health and the environment, while still being able to feed ten billion people on the planet. We need to find a way to develop our diet in that direction," she says.

In two studies conducted by Liselotte Schäfer Elinder's research group, both published in 2020, the school meals in the municipalities of Botkyrka and Uppsala were improved regarding nutritional content and greenhouse gas emissions. For four weeks, the children ate a diet that was kind – not only to the planet and our bodies – but also to the wallet.

“We have developed a method, ‘OPTIMAT’, with which we can optimise meals. This means taking into account many things at the same time, nutrition of course, but also greenhouse gas emissions and costs. Greenhouse gas emissions were reduced by 30 to 40 per cent without the pupils wasting more food– and this didn't cost more, on the contrary, it was a little cheaper,” she says.

Overall, the pupils were satisfied, although this did not apply to all the children. Liselotte Schäfer Elinder now hopes that more municipalities will test this method.

“Many municipalities have their own targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and all regions in Sweden have targets for improving public health and reducing health inequalities. By optimising public meals for health and the environment, you can achieve several objectives in one go,” she says.

It is up to each municipality and its education administration whether they join the project.

“Emissions from all public meals in the country actually represent a relatively small percentage of total food emissions, but we believe that this can have a strong signal effect,” she says.

Liselotte Schäfer Elinder believes that starting with children's eating habits is the right way to go.

“We believe that the school food we offer our children has a strong educational effect. Studies show that dietary habit track from childhood to adulthood,” she says.

Food preferences can be changed

It is perhaps more difficult to change your eating habits once you are an adult. However, Janina Seubert, who has performed both behavioural and brain imaging studies on adult volunteers, is convinced that it is possible to change food preferences as an adult. We just need to find out more about how our brain works and what the associations between smell and taste are like. In some studies which Janina Seubert and her colleagues have performed, the adult volunteers lay in an MRI camera while they could smell and see pictures of food.

“If you see a food product and smell it at the same time, you get strong brain activity in both visual brain areas and the parts of the brain that are involved with smell. If smell and image fit together, you usually like that smell. But if you can smell fish at the same time as a picture of an ice cream appears, normally you do not like the smell of fish, even if you like fish otherwise,” she says.

Insects, which contain a lot of protein, have sometimes been identified as a sustainable alternative to meat and since October 2020 for a transitional period – and pending a final decision from the European Commission – it has been legal to sell certain types of whole insects as food in Sweden. But how easy is it for us to learn to eat insects?

According to Janina Seubert, we are genetically conditioned to react with disgust towards food that looks rotten.

“It can be difficult for us to learn to eat insects, which move in a wriggling way, or other food that looks slimy or shiny. Above all, it can be difficult for adults, which is also because many have developed a fear of insects that is so strong that it borders on phobia,” she says.

But it is not impossible, she thinks.

“If we see our friends eating insects, we might be able to build up the courage to try it ourselves. This can probably work better in children, as they usually haven't had time to build up an insect phobia and in addition, children tend to learn more from their social environment,” she says.

If adults want to try to learn to eat insects or change their food preferences in other ways, it is best to start with what creates the least disgust, otherwise it can have the opposite effect.

“Sometimes food can taste better and better if you experience it more often. This doesn't work with disgusting food; this only gets worse,” she says.

In many studies, repetition has proved to be good when getting acquainted with new tastes. Previous research has shown that sugar can help make us like new tastes, but a study by Janina Seubert and her colleagues questions this. In the study, which has not yet been published, the researchers examined whether individuals could learn to like an unfamiliar smell and taste, which they had to take in the form of a chewing gum three times a day for five days. Some of the study participants also got a sugar taste in the gum.

“We thought there would be a big effect if the new smell and taste were combined with sugar, but that’s not what happened. Instead, we saw that you start to like all smells more, if you are exposed to them for a long time, but not because they are combined with sugar.

Vaguely familiar smell and taste experiences

When we get to look at and smell semi-familiar foods, the brain reacts in a different way than when we look at something that we think is disgusting or super delicious.

“If you are not sure if you recognise the smell, the prefrontal parts of the brain, which are related to decision-making, become superactive. Here we have a chance to change perception, we are more open to cognitive influence. In one experiment, we used ‘vaguely familiar variations’ of familiar food, like lemonade with a little chicken aroma, which produces a ‘somewhat odd lemonade’,” explains Janina Seubert.

“I think you can compare the lemonade with the chicken aroma with something like oat milk, which some people probably also interpret as ‘somewhat odd milk’,” she says.

The fact that the brain starts working like this around food or drink which is neither really familiar nor completely unfamiliar to us, means that there is the potential to help our taste development along the way,” she says.

“If we want to influence how we eat, I think we need to work with vaguely familiar smell and taste experiences,” she says.

In an ongoing study, she is now investigating whether there are circumstances in the environment around the meal that can help drive us in the direction of more desired food preferences.

“Maybe it's a little easier to learn to like blue cheese in a really nice restaurant. Or to learn to like new and more low-calorie food when you're not so hungry,” she says.

Many people, especially young people, have switched to a more plant-based diet.

“We see in the statistics that meat consumption is declining, but far from enough. That is why strong efforts and political decisions are needed. We live in a democracy and have the power to elect decision-makers who make wise decisions. We must develop our eating habits so that they become healthier and more sustainable – and it is urgent. I think most people realise that,” says Liselotte Schäfer Elinder.

How to eat sustainably

What you can eat every day

- (energy intake: 2,500 kcal):

- Rice, wheat, sweetcorn: 232 g

- Potatoes: 50 g

- Vegetables: 300 g

- Fruit: 200 g

- Dairy products: 250 g

- Beef, lamb and pork: 14 g

- Chicken: 29 g

- Eggs: 13 g

- Fish: 28 g

- Legumes: 75 g

- Nuts: 50 g

- Unsaturated oils: 40 g

- Saturated oils: 11.8 g

- Added sugar: 31 g

Source: The Eat-Lancet Commission, which has concluded that if everyone ate like this, there would be enough food for 10 billion people. The diet is intended to be kind to both the planet and our bodies.

More reading

Photo: Getty

Photo: GettyThe tricks that work for picky children

Being picky about food is common in children. Parental frustration can sometimes be high, but don't give up, says Paulina Nowicka, professor in food studies, nutrition and dietietics. Children can learn to eat a more varied diet.