Survive childhood cancer at a reasonable price

Four out of five children diagnosed with cancer survive. It’s a fantastic achievement. But many survivors suffer side effects of their cancer treatment later in life. Where previously the aim was to survive at all costs, the aim is now increasingly to survive at a reasonable price.

Text: Fredrik Hedlund, first published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap No 3/2016

EVERY YEAR, around 300 children are diagnosed with cancer. That’s almost one child every day. And it’s very seldom possible to say why. Adults diagnosed with cancer have often had a whole life to expose their body to cigarette smoke, alcohol and all sorts of carcinogenic foods that might have triggered the cancer. In many cases, cancer in adults is a type of lifestyle disease. But there are examples of children being born with cancer when they have not had a chance to have any sort of lifestyle – and yet they still get cancer.

So it is perhaps not so surprising that the types of cancer that affect children are very different from those that affect adults. The range of cancers, for example, is completely different. In adults, 60-70 per cent of all cancers arise in glandular tissue, for example in the breasts, prostate, lungs or stomach/bowel. But for children, cancer in glandular tissue represents only just over one per cent of all cases.

There is also a big difference between the numbers of people affected. Even though there are many fewer children than adults in our society, the differences between the numbers affected is still striking. In any given year, around 300 children are diagnosed with cancer while around 60,000 adults suffer the same fate. That means that for every child diagnosed with cancer, 200 adults get the same diagnosis, and so cancer in children represents only half of one per cent of all cancer – that’s both good and bad, as it turns out.

But for anyone affected, this information is of course completely impossible to take in, both for the child themselves and for the parents and any siblings. It is hard to think of anything worse than one’s own child, sister or brother getting cancer.

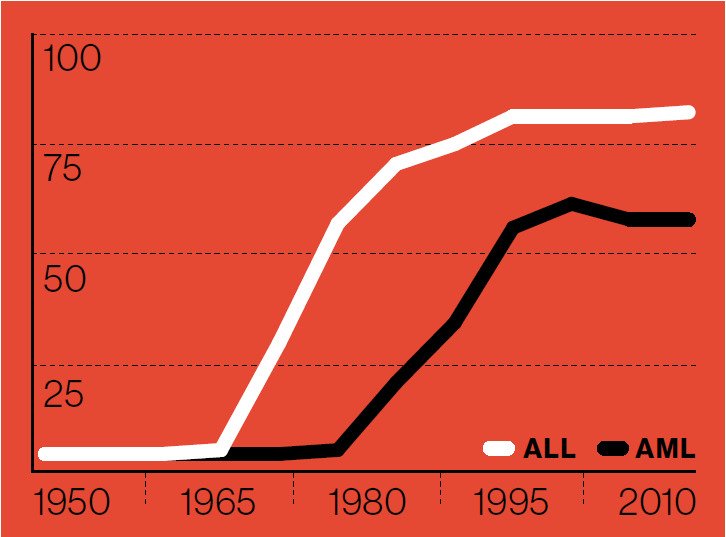

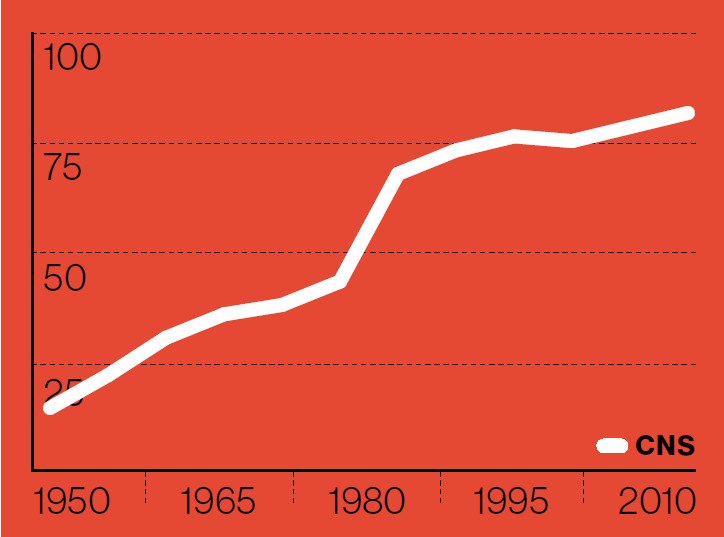

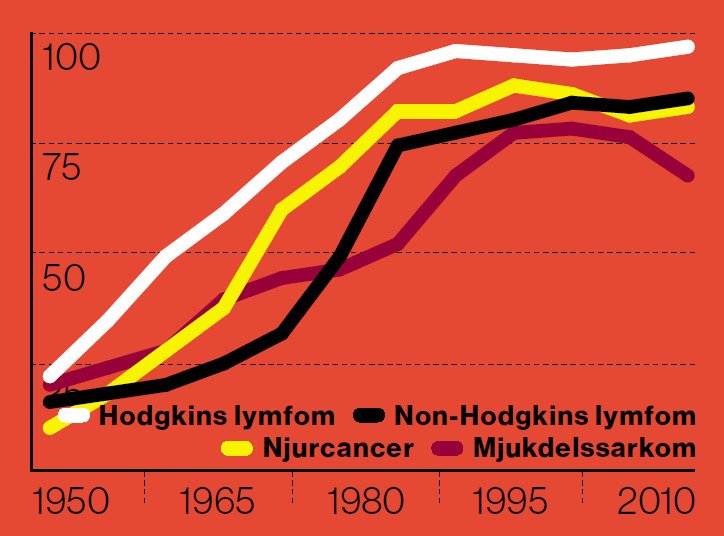

But there are other figures in this context that may be easier to absorb. Since the 1970s, there has been a dramatic improvement in survival rates for almost all forms of childhood cancer. Back then, of ten children diagnosed with cancer, on average only one or two survived; now, eight out of ten survive.

This is a medical development that has largely happened without any major medicinal breakthrough in treatment – the factors in this positive trend are completely different.

“The most important factor is that we started to treat the children,” says Mats Heyman, paediatric oncologist, senior lecturer and senior researcher at Karolinska Institutet and responsible for the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry. “There was a time when people thought that children with cancer that could not be cured by surgical means should not have any treatment at all. Leukaemia patients comprised a third of all childhood cancer patients and it was generally considered unethical to treat them. So they were given no treatment, just symptomatic relief. Up until some point in the 1970s, paediatricians thought it was pointless to treat them as they were going to die anyway and treatment would only prolong their suffering.”

The Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry contains ongoing information about every child diagnosed with cancer in Sweden – what treatment they get and how successful it is. The Registry has been in existence for a long time. It started in the early 1970s by registering every child diagnosed with leukaemia, and information about other childhood cancer cases was added to it at the beginning of the 1980s. The Registry is funded by the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation and, since 2012, when it became a National Quality Registry, also by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKL). This, thinks Heyman, is another reason for the positive trend.

“The other factor that has played a huge role in this dramatic improvement is our approach to paediatric oncology,” he says. “Although initial outcomes were terrible, we nevertheless tried to evaluate them systematically.”

That enabled paediatric oncologists to compare different forms of treatment and create what became known as treatment protocols, which have been gradually developed and improved. Put simply, doctors have learned over time how to use the treatment options available – surgery, radiotherapy and drugs – to achieve the best possible outcomes for the children. To a large extent, this has meant taking the risk of using a full dose of chemotherapy on children; strangely, children can often withstand much more than adults can.

“The element of the treatment protocols that led to this substantial increase in leukaemia survival rates was the move from somewhat cautious treatment to extremely intensive treatment,” says Hayman.

In the case of leukaemia, which accounts for a relatively large number of childhood cancer diagnoses, Swedish paediatric oncologists have been able to develop their own treatment protocols, but for many types of cancer the number of children affected in Sweden is very low. The oncologists have therefore joined treatment groups that have evaluated children in the Nordic countries, or in the whole of Europe, and in some cases the whole world. This has provided a sufficiently large body of evidence to facilitate swift progress in the development of the treatment protocols.

However, it now seems that we have come as far as we can in the current circumstances. After the sharp increase in survival rates during the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, a plateau has been reached, and, generally speaking, the last 20 years have not seen much change in terms of survival rates for childhood cancer in Sweden. It became clear that you could only intensify the treatment up to a certain point; after that it became too intensive. That started to become noticeable in the outcomes.

“Those who did not survive did not die simply because their illness got the better of them, it was also because treatment had become so intensive that we lost a number of patients because of it,” says Heyman.

In that situation, of course, you have to step back.

Instead, over the past 20 years, researchers have become more and more interested in how life goes for children who survive cancer and grow up, e.g. what sort of effects the treatment has in later life. And unfortunately researchers have found that things do not always turn out so well. As many as 60-70 per cent of survivors experience at least one complication in later life, and just under half of these complications are serious or even life-threatening. While it certainly saves the child from the cancer, the intensive treatment puts a major strain on the body’s systems.

“We have seen that children who survive cancer are at greater risk of diabetes, cardiovascular problems, hormonal imbalances, brain disorders and secondary tumours,” says Klas Blomgren, Professor of Paediatrics at Karolinska Institutet and paediatric oncologist and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital.

He has taken a particular interest in children with brain tumours, a form of cancer that has been shown to put strain on the brain in a number of different ways.

“In the first place, there is the effect of actually having a tumour in the brain; having a lump in the brain is just not good,” he says. “Secondly, there may be consequences from the operation when the head is opened up to remove the tumour. Then there are the side effects from chemotherapy and radiotherapy. There are side effects from all four of these, but the radiotherapy is the main villain of the piece.”

This is because a child’s brain is far from fully developed. In studies involving animals, Blomgren has been able to show that the radiotherapy that kills cancer cells that are dividing also stops the formation of new neurons from stem cells in the brain, something that has consequences for the brain’s development.

“It takes about 20 years for a brain to develop and anything that isn’t fully developed is very badly affected by radiotherapy,” he says. We now know that the younger the child, the more severe the consequences of the radiotherapy. Normally we no longer even contemplate radiotherapy for children aged four or under.”

In the worst case scenario, the effects of radiation and the other risk factors lead to a brain that functions less well than it should.

“Patients run the risk of cognitive side effects such as poorer memory, powers of concentration and processing speed,” he says. “They may find it difficult to cope with education or training and to function in social settings. Patients can easily become isolated and lonely and may continue to live at home with their parents and not have a partner and family.”

He notes that views on treatment have changed quite a lot in the last 20 years.

“In the past, the aim was a cure at any price. Now, it’s more a cure at a reasonable price,” he says. “The concept of refraining from radiotherapy when patients are very young is an example of that sort of balance. The more the brain is able to develop before radiotherapy is carried out, the better.”

At the same time, this is a balancing act that must be approached with caution.

“We have to be careful that we don’t reduce the level of treatment so much that the tumour returns,” he says.

The systematic approach is thus additionally tasked with evaluating the adjustments made to the treatment protocols in terms of both survival and late complications. One difficulty with that is that monitoring late complications inevitably takes quite a long time.

But there are other developments that are very likely to improve the treatment protocols. In May this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a completely new classification system for brain tumours. For the past hundred years, brain tumours have largely been classified according to their appearance under the microscope. But that system has now been complemented by a sort of genetic tumour map that will be of crucial importance for how tumours are subdivided and treated. Suddenly it is possible to distinguish different types of tumour that look identical under a microscope but that respond to treatment in completely different ways.

“Some tumours look quite similar, but some patients do not fare at all well while others survive,” says Blomgren. “This new classification shows the tumours in distinct groups that correspond really well to a patient’s chances of survival. And that’s important, because if you have a patient whose tumour has a nearly 100 per cent survival rate, you need to be careful with radiotherapy, which you know will give them lifelong disability, or heavy-duty chemotherapy, which is also distressing and can affect aspects such as a patient’s ability to have children in the future. This is a minor revolution in the treatment of brain tumours.”

The new classification system has redrawn the map for brain tumours and will make it easier to choose the right treatment for the tumour. It is hoped that it will further increase survival rates, but it will take some time before that can be verified.

“This is something completely new, and we won’t see the results of it for another five or ten years,“ says Blomgren.

But more can be done right now to help survivors of brain tumours. Blomgren explains that up to now they have tested children about a year after their treatment has finished to determine whether they have any cognitive impairment, but they have now realised that this is far too late. Their aim is now to involve the rehabilitation team at the point when treatment starts so that the child is monitored the whole time and any difficulties that arise can be identified immediately.

“We now know that the brain is so much more malleable and susceptible to influence than we previously thought,” he says. “So any intervention should come at quite an early stage. If you simply allow the damage to develop, peak and then subside, you have less opportunity to combat it. You have to intervene earlier.” Rehabilitation might sound dull, but that need not be the case. Blomgren and other researchers have been able to demonstrate that physical activity is extremely effective in healing damage to the brain and improving performance.

“Physical activity is something that has quite a lot of appeal and few side effects, but we don’t yet really know how we should be using it – how much should we prescribe and how do we get patients to do it?”

From a small-scale study undertaken jointly with researchers from Gothenburg, he was able to show that 45 minutes per day of actively playing video games with motion sensor consoles (Wii) over a period of 10-12 weeks significantly improved children’s coordination and everyday levels of functioning.

“Physical activity significantly increases the formation of new neurons from stem cells in the brain, and there are other benefits including a better memory,” he says. If there are cells remaining, physical activity can reactivate them.”

According to Blomgren, an option that is not used very much but could probably be used more is ADHD medication, i.e. central nervous system stimulants.

“Everyone who has had damage to the brain experiences mental fatigue to a greater or lesser extent.,” he says. “It may mean they can only do 20 per cent of what a healthy person can manage, then just collapse and have to sleep.”

There is very little understanding about this in the community when children are growing up and expected to fend for themselves. Employers and the Swedish Social Insurance Agency are seldom aware of the issue of late complications.

“And perhaps that is not so surprising as there are not many patients in this category, but there are getting to be more and more of them,” says Blomgren. “Childhood cancer survivors are a group that did not exist before, but it’s a group that is now increasing in number.”

But it is possible that he may have an even better solution to the problem of brain damage resulting from radiotherapy. He has discovered that lithium, a humble element normally used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, protects brain cells against radiation, but does not protect cancer cells. So far this has only been demonstrated in animal testing, but the effect he noticed was significant. The next step is to give lithium to children with brain tumours that require radiotherapy. The aim is for the lithium treatment to be administered during the actual radiation and for the following six months. Researchers plan to start a first study around the turn of the year with the involvement of childhood cancer patients in Stockholm, Copenhagen and Paris.

Another innovation affecting all types of childhood cancer is the newly-agreed National Care Programme for long-term monitoring of childhood cancer. Provisions include making it compulsory for the country’s six university hospitals, which all have a paediatric oncology centre, to establish special clinics for late complications and to offer children who have had cancer a structured monitoring programme. There are already clinics of this kind in Lund and Gothenburg but not as yet at the other university hospitals, and so not in Stockholm either.

“No, not in the same way,” says Blomgren. “But it is urgent, as these patients have extremely specific and special needs, so they need help from someone who understands why those needs have come about. Otherwise they can easily fall between two stools. Particularly when they turn 18 and have to manage their healthcare by themselves; not everyone can handle that.”

And the need is growing. Sweden now has over 10,000 survivors of childhood cancer, and the oldest are starting to reach their 30s and 40s.

Recently, researchers identified and investigated a previously little-known late complication in around 50 male childhood cancer survivors who were aged between 25 and 38 and who were compared with control subjects of the same age. They were all survivors of a blood cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), which was previously often treated with intensive chemotherapy and general radiotherapy to the brain, something that affects the cells of the entire brain. These days, patients are not treated in this way, but the men in the research project had had the more aggressive treatment to a varying degree.

It became apparent that the sex lives of these survivors were much worse than those of the men in the control group. Their sexual function, sexual behaviour, orgasms and libido were significantly worse. They were also more likely to be single and childless.

But this was not because the men treated for cancer were less interested in sex or had erectile problems, which is something that can affect adult cancer patients following radiotherapy. Where masturbation was concerned, for example, there was no difference between the groups. It seems instead that it is relationships with potential sexual partners that is the major difference.

“We know from earlier studies that a high proportion of cancer survivors are socially passive as young men in comparison with their contemporaries,” says Kirsi Jahnukainen, paediatric oncologist and visiting professor at Karolinska Institutet. “They also leave home later than those who have not had cancer. We suspect that it is this particular group that remains single.”

Radiotherapy treatment to the brain can affect a patient’s ability to learn and how they think and behave, she says. But at the same time, she points out, they have not been able to find any evidence that it was the radiation that was the cause, as those who had not had radiotherapy treatment to the brain had an equally poor sex life. In addition, the study was quite a small one, and a more comprehensive study might give a different result.

But Jahnukainen thinks that there are other factors at play. When a child is diagnosed with cancer it affects relationships in the whole family, and the child becomes extremely dependent and closely tied to their family. When boys become young men, this can affect how they manage their early love life and relationships with their contemporaries. The fact that they leave home later also indicates that they are more tightly bound to their family. But it might also be the case that the treatment itself limits opportunities for socialising.

“The treatment takes two or three years – if you have a recurrence that will take five years – and meanwhile life goes on for your contemporaries,” says Jahnukainen. “That very sensitive first contact with girls perhaps doesn’t happen in the way it should, which can affect relationships with women of the same age later on.”

The research is currently unable to say what it is that actually causes male cancer survivors to have a poorer sex life, but Jahnukainen’s study shows that the problem is a major one that needs more attention.

For those male survivors of childhood cancer that perhaps recognise themselves in Jahnukainen’s description, it is of course problematic that the special late complications clinics prescribed by the National Care Programme are not yet in place in all parts of the country. Nevertheless, Jahnukainen’s advice to those who feel they’ve been affected is to visit their medical centre as a first step. Sexual difficulties following cancer treatment may also be due to a lack of testosterone. This was the case for a number of men in the study, and this can be treated quite easily with supplementary testosterone. Medical centres can also help in getting records from the hospital where a patient was treated as a child, as it is important to know the type and extent of the treatment provided.

Jahnukainen says that increasing our knowledge about this connection can in itself have some effect.

“I think it is important to understand that this is a symptom of the treatment, that people realise that ‘it’s not just me that’s no use’,” she says. “People may feel better once they know that.”

On the whole, though, the situation is positive. Survival rates for childhood cancer have risen at an incredible rate from 10-20 per cent to 80 per cent over only a few decades. This is a fantastic development for all children diagnosed with cancer and their parents, siblings and other relatives. Or almost all, because, without belittling the successes of the past 40-50 years, 20 per cent of children still die. And that’s been the case for 20 years. Paediatric oncologists and researchers have gone as far as they can with the existing treatment. Heyman says that the realisation that the treatment can also cause long-term damage can help reduce the side effects, but that not much more can be done to improve the outcome of the treatment available today.

“What we need now, to help the final 20 per cent and get from 80 to 100 per cent, is a qualitatively new type of treatment,” he says. “That means we need a different understanding of the illness and an ability to provide treatment targeted at something specific to it. That usually means new drugs, drugs that are based on a better understanding of the illness.”

But there is a problem here – or, as Heyman puts it diplomatically:

“Paediatric oncologists have a complex relationship to pharmaceutical development.”

He explains that it is in principle financially unfeasible to produce a new drug specifically aimed at childhood cancer.

“Of course we dream of identifying specific drugs that can address the genetic changes in the cells of a child with cancer, but there almost always has to be a similar illness or at least a similar principle for adult cancer,” says Heyman. “Otherwise, there is no pharmaceutical company in the world that can afford to develop such a drug.”

Childhood leukaemia

Leukaemia used to be called ‘blood cancer’, but in fact the illness arises in the bone marrow. Immature precursors to white blood cells in the bone marrow start to divide uncontrollably, preventing the production of healthy blood cells. The leukaemia cells may gradually spill out into the blood stream and spread to other organs of the body. There are several different types of leukaemia, but the two main types in children are acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukaemia represents around 30 per cent of all childhood cancer cases.

CNS tumours

Solid tumours found in the central nervous system (CNS), usually in the brain but more rarely in the spinal cord, are called CNS tumours. Their level of aggression varies from benign to very malignant, so the prognosis can vary a great deal. The four most common types of brain tumour are astrocytomas, which can be found in any part of the central nervous system, brainstem gliomas, which start in the brain stem, medulloblastomas, which start in the cerebellum, and ependymomas, which may be found in either the cerebrum or the cerebellum. CNS tumours represent over 25 per cent of all cases of childhood cancer.

Other tumours

In addition to leukaemia and cancers of the brain and central nervous system, there are a large number of other types of tumour that can affect children. These are normally brought together under the heading ‘other solid tumours’ and together constitute the largest group of tumours in children, but they include a very large number of different types of cancer, several of which are uncommon. The most common are lymphoma (mainly Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin), which affects twelve per cent of children, and kidney cancer and soft tissue sarcomas, which each represent just under six per cent of cases.