Results from the COMBAT-MS study

COMBAT-MS (COMparison Between All immuno-Therapies for Multiple Sclerosis) was an observational drug trial that was finalized during 2022. The purpose of the study was to determine long-term outcomes for those starting a first disease-modulating drug for relapsing MS between 01/01/2011 and 10/31/2018, or who made a first drug switch from a MS drug to another during the same time period.

Background

MS is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, where those affected are at risk of temporary or permanent neurological impairments. To reduce this risk, a number of different drugs that modulate the immune system in different ways have been developed, in turn reducing inflammatory disease activity. To be approved, it is required that several studies (drug trials) have been carried out in which the efficacy and safety have been established. In traditional drug trials a lottery ticket determines if someone is assigned to active drug or a control treatment, where neither the study participant nor the study doctor knows which it is. These types of trials are called double blinded randomized controlled trials and are considered to give the most robust evidence for effectiveness and safety of a drug, since you don´t need to account for placebo effects or other factors that can influence treatment responses. However, there are also important limitations. For example, due to costs and ethical reasons, a controlled trial can run only for a limited time period, in MS typically not more than two years, and with a limited number of participants. It is also rare to compare the effect of several different drugs at the same time. Collectively, this makes it difficult to draw robust conclusions about long term benefit and risk – the benefit-risk balance – across different treatment options.

Many patients also are not eligible to join or decline participation in randomized trials. This makes it more difficult to extrapolate results to real world MS populations. A complementary way to study effect and safety of drugs is to do registry studies. Advantages with this type of studies are that they can be conducted over longer periods of time and include many more persons. However, there are also important drawbacks. Most important, it is more difficult to attribute effects (positive or negative) to the drug, since people who start different treatments might differ in aspects that impact treatment outcomes. Together, this means that the treating physicians do not have optimal evidence for recommending a certain type of treatment, especially when this also should include individual factors. Specifically looking at MS drugs, we primarily have information on to what degree they reduce the risk of relapses and the appearance of lesions – plaques - visible with magnetic resonance imaging. In contrast, information on how MS drugs affect the risk of developing neurological impairment or impact quality of life, especially over longer periods of time, is still scarce. This is problematic since these two aspects are the ones ranked highest by people with MS and their treating neurologists. Incomplete evidence likely is an important reason why drug preferences differ so much between different countries, regions and clinics. In fact, place of residence has greater influence on MS drug choice rather than what type of MS or individual characteristics you have. One aspect that makes MS clinics in Sweden and certain other locations, including Kaiser Permanente Southern California, different is that a relatively large proportion of MS patients initiate treatment with rituximab (Mabthera, Rixathon, Truxima). Rituximab is a drug approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, but with no formal approval for MS. The overall goal of the COMBAT-MS study has been to collect and analyze data relating to the benefit-risk balance with different drugs over a longer period of time. In particular, we wanted to see if there were advantages or risks with rituximab compared with regular MS-approved drugs.

How was the study conducted?

COMBAT-MS was an observational drug study conducted at all of Sweden's neurological university clinics. The study was funded by an American federal foundation (PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) whose overall purpose is to support high-quality scientific projects that improve treatment and care in various disease states. Therefore, COMBAT-MS has no commercial interests. One of the most important aspects of COMBAT-MS was that we chose very liberal criteria for participation, thereby aiming to include as many people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) as possible. This also means that results are more likely to be of relevance for the heterogeneous real-world group of people with RRMS. Between 06/02/2017 and 06/30/2019, 3522 people consented to participate in COMBAT-MS, which is more than 80% of those who met criteria for participation. This number corresponds to approximately half of all MS patients in Sweden in this category, where the remaining half are followed at neurology clinics outside of university hospitals. The main objective of the study was to evaluate the outcome for those who started a first drug treatment (treatment naïve group) or who made a first drug switch (switch group), where some people could contribute information to both groups if they had switched treatment during the observation period. Overall, this meant that we had information of 2642 individuals in the treatment-naive group and 2531 in the switch group. Since results were compiled and compared at the group level and results are less reliable with small group sizes, we excluded treatment groups with less than 100 individuals. Therefore, not all drugs currently available were analyzed

Given the input from our study stakeholders the two most important study outcomes were proportions with increasing disability at 3 years of follow up (defined as an increase in a rating scale for neurological symptoms lasting at least 12 months), and change in patient-reported quality of life over the same time period. The study also had a number of so-called secondary outcomes that reflected other aspects of how the disease state evolved. To make comparisons across different drugs more reliable, results were adjusted for various factors that could impact outcomes, such as sex, age, place of residence, level of education, disease characteristics at start of treatment, disease duration, and comorbidity.

What were the results?

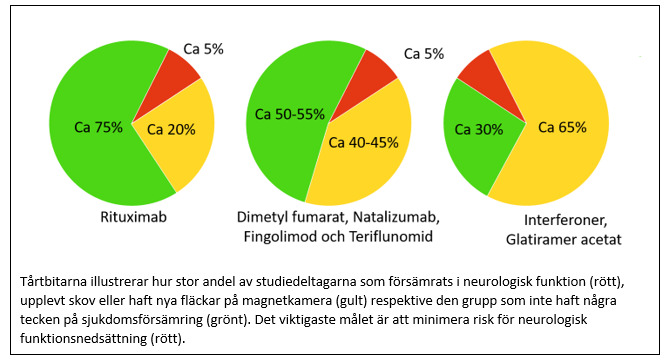

To our surprise we found that initial drug choice did not affect the risk of suffering an increase in neurological disability or a negative impact on quality of life! At the same time, results were also more positive than we had expected, as only one person in 20 experienced worsened neurological functions at 3 years after starting treatment. A more limited worsening of neurological functions was reported by one in five, but an equal proportion instead reported improvement. Another positive result was that a majority reported improved quality of life compared to at start of treatment.

However, when looking at other outcome measures larger differences between drugs were evident. Thus, the risk of experiencing a relapse in the treatment-naive group was lowest for those treated with rituximab (less than 1 in 10 over a period of 3 years), while the corresponding figure for those treated with dimethyl fumarate or natalizumab was 1 in 5 over the same time period. Those who had started treatment with interferons or glatiramer acetate had the highest risk, almost 1 in 3. Corresponding differences were also found in the switch group, where less than 1 in 10 experienced a relapse with rituximab, 1 in 10 with dimethyl fumarate and 1 in 5 with fingolimod, natalizumab or teriflunomide.

Differences in how likely it was to remain on treatment with different drugs were also large. The probability to remain on treatment was greatest with rituximab (9 out of 10 in both groups). For dimethyl fumarate, natalizumab, fingolimod and teriflunomide, around half remained on treatment at 3 years, while the corresponding figure for interferons and glatiramer acetate was only 1 in 3.

Fact box - Criteria

COMBAT-MS

Inclusion criteria

- • Initiated a first MS drug (treatment naïve), or made a first MS drug change (switch) between January 1, 2011 and October 31, 2018

- • Followed at one of Sweden's university clinics

- • Provides consent to participate

- • Expected to be able to complete the study assessments and have decision-making skills.

- • Aged ≥18 and ≤ 75 years at the date of signing the informed consent.

- • For women of childbearing age: have received information about potential drug risks during pregnancy and which types of contraceptives are considered safe based on the selected MS drug.

Exclusion criteria

- • Progressive forms of MS at treatment start.

- • Other neurological or non-neurological conditions that may affect the ability to conduct the study or evaluate the study assessments.

- • People with contraindications to the use of for example contrast agents used in MRI examinations.

- • Ongoing participation in other trials with blinded study medication or that interfere with the study protocol.

One important fact to consider when interpreting the results is that the initial drug choice determined the group you belonged to. For example, a majority of those who started interferons or glatiramer acetate had switched to other treatments at the time point of evaluation at 3 years, but where still assigned to be on the initial treatment when presenting the main results. It is difficult to speculate how study results would have looked if people had been forced to remain on the initial drug choice. A balanced interpretation is that the initial drug choice does not appear to affect the disability and quality of life outcomes at 3 years if one is allowed to change treatment due to lack of effect or side effects.

Fact box - Drugs

Treatments included in the analyses

Newly started drug treatment (Treatment naïve group)

- • rituximab (Mabthera, Rixathon, Truxima)

- • dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera)

- • natalizumab (Tysabri)

- • interferon (Rebif, Avonex, Betaferon, Plegridy, Extavia)

- • glatiramer acetate (Copaxone)

Made a first drug change (Switch group)

- • rituximab (Mabthera, Rixathon, Truxima)

- • dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera)

- • natalizumab (Tysabri)

- • fingolimod (Gilenya)

- • teriflunomide (Aubagio)

We also performed a separate analysis of patient-reported treatment satisfaction on the ongoing treatment. Here, patients who had treatment with rituximab tended to report increased treatment satisfaction compared to other drugs, although differences were relatively small.

What happens after the first 3 years?

We also analyzed outcomes up to 9 years after start of treatment. Since only a smaller proportion of study participants contributed data for that long, results are less precise. Also here we found an unexpectedly small proportion with worsened neurological disability. At 9 years, barely 1 in 10 in the treatment-naive group and only bit more than 1 in 10 in the switch group had experienced disease worsening. Also here the risk was not affected by the initial drug choice. However, differences across drugs in risk of experiencing a relapse and the probability of remaining on treatment were large and similar to the pattern at 3 years. Overall, the results show a more positive picture regarding disease evolution than we had expected when the project was initiated. A reasonable interpretation is that early initiation of treatment at disease onset in combination with treatment switching in the event of any signs of lack of effect or side effects, have contributed to these positive outcomes.

Side effects and safety

The risk of side effects is an important factor to consider when selecting an MS drug. A unique aspect of the COMBAT-MS study was that we were able to include important safety outcomes by extracting data from high quality national health registries available in Sweden and KPSC. In this analysis we saw that highly effective MS drugs seemed to increase the risk of infections that require hospitalization in open or inpatient care. Compared to interferons, rituximab increased this risk by around 70%, while the risk increase for fingolimod and natalizumab was less pronounced. These two drugs, on the other hand, increased the risk of herpesvirus infections and shingles compared to interferons and rituximab. However, the overall absolute risk of infections was limited. For COMBAT-MS participants in the treatment-naive group, the risk of an infection requiring hospitalization was about 1 in 100 per year for those treated with rituximab, dimethyl fumarate, or natalizumab, and about half that with interferons or glatiramer acetate. In the switch group, the risk was twice as great with rituximab (2 in 100 per year), which was significantly higher than for the other treatments (dimethyl fumarate, natalizumab, fingolimod and teriflunomide). The risk of cancer or more serious cardiovascular disease did not appear to be affected by any MS drugs. Only 12 (treatment naïve) and 16 (switch group) were diagnosed with malignant cancer during the observation period. This low number means that it is difficult to compare across drugs. However, in a previous study where we analyzed all people with relapsing MS in Sweden, we could not find any significantly increased risk of cancer linked to the MS disease itself or the studied MS drugs (interferons, rituximab, fingolimod, natalizumab) compared with the general population. The number of serious cardiovascular disease events, such as stroke or myocardial infarction, in COMBAT-MS participants was even lower than the number of cancers, with no signal associated with any specific MS drug. Overall, these results suggest no or low risks of more serious treatment side effects, with the exception of an increased risk of hospital-treated infections with rituximab, and herpesvirus infections with fingolimod and natalizumab, compared to interferon treatment.

Many people diagnosed with MS are women of childbearing age who may want to plan a pregnancy. In this situation one needs to consider both a potentially negative effect of the MS drug on the child, but also that interruption of treatment may increase the risk of MS relapse for the mother. Since we still have limited information on the safety of MS drugs during pregnancy it is often recommended to stop treatment before pregnancy. Within the framework of the COMBAT-MS project, we conducted several sub-studies on this topic, using data both from the MS register and national health registers.

In these studies we could not find any evidence of increased risks for fetal malformations or other more serious effects on the child with exposure to MS drugs. However, the mothers’ risk of relapse after giving birth to their child was significantly lower among those who had been treated with rituximab before pregnancy, both compared to those who were treated with natalizumab before pregnancy and those who were untreated. These results indicate that treatment with rituximab may have advantages for women who are planning a pregnancy and want to minimize the risk of disease worsening after giving birth.

Conclusion

The COMBAT-MS study has shown that the risk of disease worsening with currently available treatments is less than we previously thought. These results are also better than contemporary data collected in other contexts and suggest that quality of healthcare impact long term MS outcomes. A positive result was also that there seems to be different ways to reach this goal, i.e., if allowing for drug switching no single treatment was better than others in avoiding increased neurological disability or experience reduced quality of life. At the same time, it is clear that a proportion of persons with MS needs new types of treatments that reduce risk of continuous disease deterioration and progressive MS. Intense research efforts are being made, but it is difficult to predict when such treatments may become available. There is also a great potential to further improve the benefit-risk balance with existing MS treatments. With better knowledge of who is at risk of having an insufficient effect or experiencing side effects with specific MS drugs, we can become better at selecting a suitable treatment from the start, i.e., to individualize the choice of treatment (also called precision medicine). Other important areas of improvement are understanding how lifestyle changes can improve the prognosis in MS. The data collected within COMBAT-MS will be an important tool for further studies to shed light on some of these aspects. All of this has been made possible thanks to the fantastic collaboration we have had with all COMBAT-MS participants from the north to the south in Sweden, especially with the challenges the COVID-19 pandemic brought, and all the extended participants in Sweden and at Kaiser Permanente Southern California in the US. A positive consequence was also that clinical follow-up routines in participating clinics have further improved thanks to the COMBAT-MS project. We look forward to continue collaborating with our patients in this important work!

- Executive Committee (EC): Project steering group

- Clinical Advisory Team (CAT)

- Scientific Advisory board and stakeholders

Glossary

COMBAT-MS: Comparison Between All Immuno-Therapies for Multiple Sclerosis

Disease-modulating drugs: drugs that affect the immune system in different ways and thus reduce the inflammatory disease activity.

MS: multiple sclerosis

Observational drug trial: Drug trial where you follow up treatment effects based on the drug choice made on purely clinical grounds, i.e. you don't let the lottery decide which treatment to give the individual person.

PCORI: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

Placebo effect: favorable effect on the disease even when treated with an inactive substance (often sugar pills) and which depends on the expected effect of the drug

For different medicines, see fact box