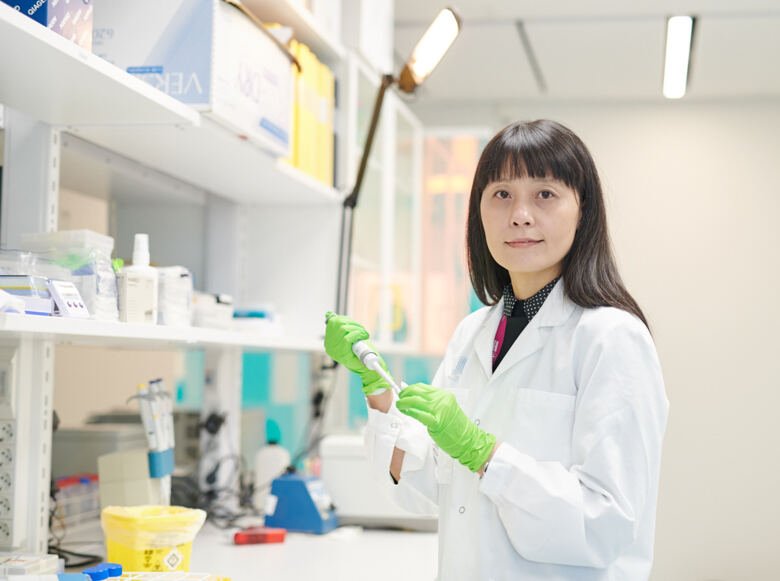

‘The lab is my frontline’

Immunologist Qiang Pan Hammarström has worked every day since late January to find medicines against the new coronavirus. With her husband and KI-colleague Lennart Hammarström, she coordinates an international research consortium that is working on three tracks to develop treatments against COVID-19.

Text: Anna Molin, first published at ki.se in April 2020.

A shorter version is published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap No 2/2020.

When did you get involved in the fight against the new coronavirus?

“I was born and raised in China and have worked as a respiratory disease specialist there. So, when the new coronavirus grew into an epidemic in late January, many of my friends and former colleagues voluntarily traveled to Wuhan, which was then the epicenter of the outbreak. I was very touched by their courage and at the same time heartbroken when one of my former schoolmates was infected and died at the frontline.”

How did it affect you?

“The stories from Wuhan were horrible. A classmate of mine worked 80 hours per week in the intensive care unit and described feeling totally powerless. There were no antiviral drugs that worked, no vaccine, nothing he could do to help. He and many of my friends put their hope in me, that I, as a researcher, would find a therapy that worked. It was then that Lennart and I decided to form a consortium with researchers from five different countries that together are working to develop antibody therapies against COVID-19.”

Could you describe what you are working on?

“We are working on three different strategies. Essentially, it is about finding the best antibodies, from recovered patients whose antibodies are purified from blood plasma and whose antibody producing white blood cells are cloned in the lab. One strategy involves using hyper immune gamma globulin, which is prepared from the blood plasma of recovered COVID-19-patients and has high antibody levels. It will be tested in clinical trials directly in people. At the same time, we are looking for leading candidates for so-called monoclonal and recombinant antibodies, and these will be tested in animal models first. Unlike those studies where they have already started giving plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients directly to those who are still sick, we are focusing on developing medicines that can be used in the near future. The downside with our approach is that it takes longer. The upside is that we could have a really effective and safe medicine that may also be given to those with weak immune systems who won’t be as protected by a future vaccine.”

Why is it important to also take a long-term approach now?

“We don’t know how long we will have to live with this virus, and therefore it is important that we focus both on immediate and more long-term solutions. When the first SARS-virus went away in 2004, the funding was cut and most of the research stopped. That was a shame because we need to find both medicines and vaccines against the coronavirus. I think we will succeed this time because there are so many researchers from different fields working on this now. Corona is all we talk about.”

On a more personal note, what’s it like to work with your partner?

“It’s fun! We talk about work day and night. Some ask me if it gets boring, but I don’t think so. We met at KI and have now been married and working together for more than 20 years. But neither of us have ever experienced anything like this before. As a scientist, I feel it is my duty to try to find a cure against this virus — I consider the lab my frontline.”

More about KI's work on COVID-19

Photo: Erik Flyg

Photo: Erik FlygSearching for a coronavirus vaccine

Matti Sällberg leads a team that searches for a vaccine against the coronavirus. "Others will be quicker, and therefore we are thinking long-term and focusing on finding a vaccine that can protect against several coronaviruses, including those that may pop up in the future," he says.

Photo: Erik Flyg

Photo: Erik FlygThe hunt for antibodies against the coronavirus

Researchers around the world are working hard to find solutions to the coronavirus crisis. Gerald McInerney, Associate Professor of Virology at KI, focuses on developing antibodies that can block the virus’ ability to infect cells.