The story about KAW's support to KI

In its pursuit of excellence and pursuing long-term goals, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation has awarded billions of Swedish kroner to researchers at Karolinska Institutet over the years. The Foundation, celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2017, has grown into one of Europe’s largest private financiers of research, and the grants awarded by the Foundation have inspired numerous careers in research.

Text: Maja Lundbäck, published in 2017.

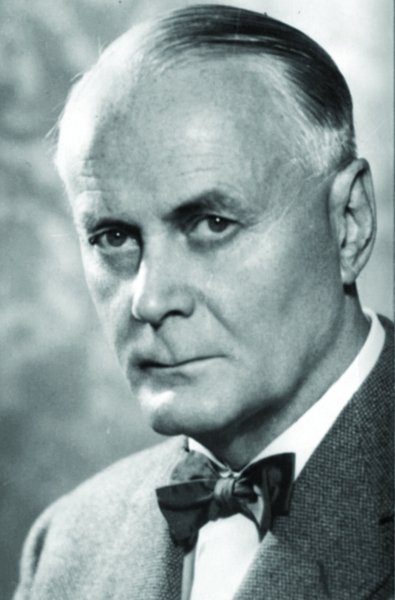

The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW) was founded in 1917, but it was not until 1940 that the first grant was awarded to a researcher from KI. The first man to attract the interest of KAW was neurophysiologist Ragnar Granit, who went on 23 years later to be awarded a Nobel Prize for his discoveries relating to colour vision.

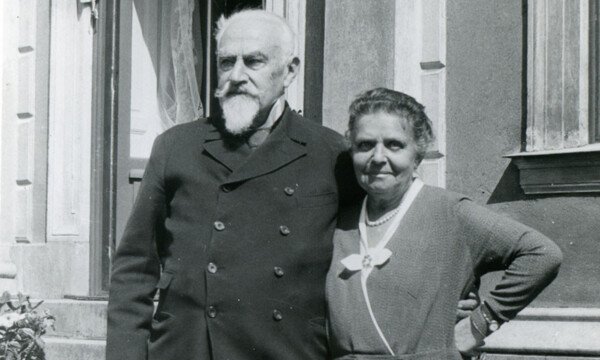

One hundred years ago, when Knut and Alice Wallenberg started their Foundation, Knut had recently been ill, most probably from exhaustion after several difficult years as Sweden’s Minister of Foreign Affairs during the raging World War. The couple had no children and therefore decided that their vast fortune should be donated to a Foundation, the purpose of which was to support projects beneficial to Sweden. Initially, grants could be awarded to different industries that were close to Knut Wallenberg’s heart.

Up to that time, none of the researchers from KI – including Herbert Olivecrona, brain surgeon and Professor of Neurosurgery – had been successful in their applications. However, all this was to change with Ragnar Granit, a Fenno-Swede, and it was thanks to Gustaf Bernhard, one of the younger neurophysiologists at KI.

Ragnar Granit actually had a professorship in Helsinki and had been granted a considerable amount of researching funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. However, when the Soviets invaded Finland in 1939, giving rise to the Winter War, life took a turn for the worse. Ragnar Granit was called up as an army surgeon. However, his yearning for a serious career within research prompted him to move abroad.

“Ragnar Granit was in his late 30s and was terrified as he stood in the doorway to the cathedral in Helsinki. As he watched the Soviet planes fly over the city, he observed the destruction of the Parliament building and University library, but also of his future as a researcher,” explains Olof Ljungström, medical historian at KI.

“He would never have ended up at Karolinska Institutet if it had not been for the war,” confirms Olof Ljungström.

History could in fact have been very different, as it was a very close call between the USA and Sweden. Given his recent experience from the new British research field of neurophysiology, it did not take long before he was offered a position as Professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“Surprisingly, Karolinska Institutet was able to ‘snatch’ Ragnar Granit from right under the noses of Harvard!” explains Olof Ljungström.

KI had also understood that Ragnar Granit was looking for a new position. Carl Gustaf Bernhard, a doctoral student in neurophysiology, was the one to suggest that KI should attempt to invite him to Stockholm. The teaching staff at KI understood the Swedish Government could not afford to fund the promising researcher while the Second World War was raging in Europe. Instead, they appealed to KAW for economic support. KAW was fully informed that the Rockefeller Foundation believed strongly in Ragnar Granit and agreed to provide financial support, but only if the Rockefeller Foundation also promised to continue funding the research.

“The fact that Ragnar Granit was able to continue his research work for the entire duration of the Second World War was thanks entirely to the grant provided by KAW, their first ever at KI and within medical research,” confirms Olof Ljungström.

Now that KAW had made their initial investments in medical research, the funding continued and became increasingly generous.

“Between 1940 and 1949, KI received more than 12 percent of KAW’s total grants. After 1950, this figure rose to more than 25 percent,” recounts Daniel Normark, medical historian.

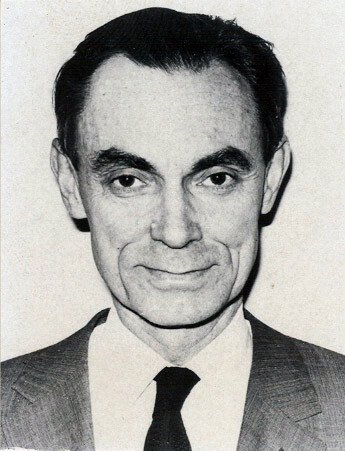

In 1953, 50 percent of KAW’s allocations budget was granted to KI in the form of a new endocrinology research laboratory to be led by Rolf Luft. He was part of a group of Jewish researchers who all refused to accept the research that had emerged in connection with the Nazi experimentation on humans.

“When Rolf Luft presented his theses several years earlier, he had been met with harsh criticism as he refused to acknowledge the existence of the German literature. He received a relatively low grade for his thesis and lost out on the docentship for which he was destined,” explains Daniel Normark.

If you did receive a low grade on your thesis that would, during this time period, indicate that you were a mediocre researcher, setting you off to a career pathway with steep hills to climb. But the initiative from KAW would come to change things dramatically.

“The financial support provided to Rolf Luft is proof that KAW has the power to change not only the future of a researcher but also a research field. Thanks to the grant provided, endocrinology became a much more extensive field. Thanks to KAW’s signal policy, a number of other parties were encouraged to invest in endocrinology,” explains Daniel Normark.

KAW would frequently turn to the USA and the Rockefeller Foundation to discover which young researchers deserved their support, and here they learned of Rolf Luft, described as brilliant, and the research field of endocrinology, described as promising. KAW listened and reacted. Over the years, KAW has financed numerous major buildings and advanced research equipment at Karolinska Institutet. However, the Foundation has not always had full control over who receives the support and for what purpose.

For many years, grants from KAW to KI were primarily awarded to Bengt Samuelsson, Sune Bergström’s doctoral student, who received a Nobel Prize in 1982, and Georg Klein, Professor of Tumour Biology.

KAW’s support to KI in selection

1917-1918

The Foundation’s Articles of Association and statutes are established.

1940

Support for Ragnar Granit (Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1967) and creation of a department of neurophysiology at KI.

1942

Research into cause of adrenal gland insufficiency.

1948

Purchase of electron microscope.

1955

Instrument for studies of cancer.

1957

Spinco electrophoresis equipment for Hugo Theorell (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1955).

1959

Laboratory building for short-term research projects on KI’s 150th anniversary.

1978

Hospital cyclotron, PET camera.

1981

Equipment for Bengt Samuelsson (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1982).

2003

Centre for kidney research.

2008

MRI equipment.

2009

Wallenberg Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WIRM).

Swedish Brain Power.

2010-2017

A large number of project grants and financing of research leaders within the Wallenberg Clinical Scholars programme, the Wallenberg Academy Fellows and Wallenberg Scholars. Find out more here.

Since it was founded in 2010, SciLifeLab, where KI is one of the host universities, has received various forms of support from KAW.

Source: Anniversary book, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation

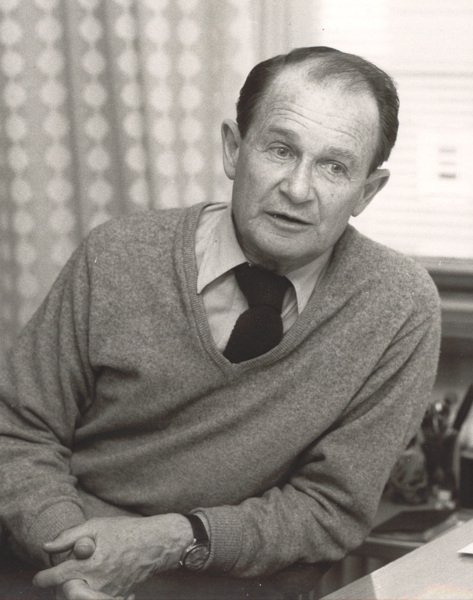

In 1959, KAW planned to make a strategic investment by assigning Sune Bergström, Professor of Chemistry and subsequently a Nobel Prize laureate, the task of providing a new building where the Foundation’s funds could be of most benefit. The building was named the “Wallenberg Foundation’s anniversary laboratory 1960”, a mobile institute that was to open the doors for younger researchers to obtain a career. However, when the building was completed, Sune Bergström had managed to stipulate terms whereby he was the one to decide who could move in.

“This was to change in 1986, by which time the Foundation planned to make a new strategic decision, expand their activities and ensure that a higher number of researchers had access to research funding,” recounts Daniel Normark.

In the years that followed, large grants were awarded to Göran Holm, now Professor Emeritus of Medicine, Lars A. Carlsson, Professor of Medicine, and Jan Lindsten, Professor of Medical Genetics, to fund each their own research programmes.

Today, KAW’s main focus – in addition to strategic investments – is on individual excellent researchers.

“KAW plays an extremely important role for basic research, without any political motives. It is important to underline how important it is for KAW to invest in individuals. They follow a long-term and sincere strategy to promote without management,” confirms Anna Wedell, Consultant and Professor of Medical Genetics at KI.

In 2013, she was awarded a major grant by KAW, and was named a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar in 2015 for her work on developing research into hereditary metabolic diseases.

“This has been of critical importance in allowing me to develop a creative and interdisciplinary group with a mix of basal basic research and large-scale genomics and clinical activities,” she explains.

Up to 2016, KAW has awarded grants totalling SEK 24 billion, of which KI has received a large share. Thanks to profitable investments, the Foundation’s capital has seen a substantial growth from SEK 20 million to SEK 90 billion. KAW is now one of the largest private financiers of research in Sweden and Europe.

On 15 September 2017, Karolinska Institutet, KTH and Stockholm University will hold the anniversary symposium entitled Molecular Life Sciences in Aula Magna, to celebrate that the KAW Foundation has promoted Swedish research and education for 100 years.