Loneliness — a danger to our health

Feeling alone is tough, and it also appears to be detrimental to our physical health, possibly to the same extent as smoking. But loneliness can be beaten, according to a Swedish study published some years ago.

Text: Annika Lund. First published in the magazine Medical Science 2015.

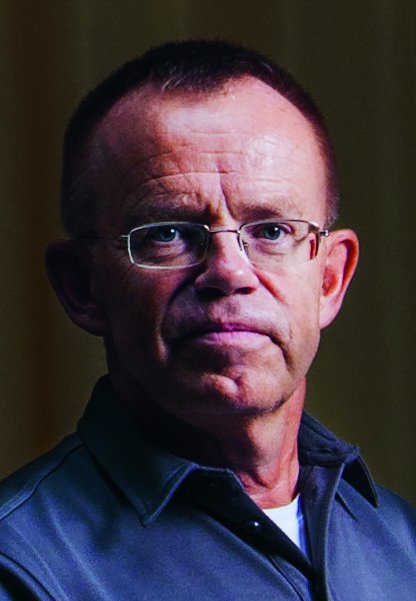

For more than thirty years, Peter Strang, Professor at the Department of Oncology-Pathology at Karolinska Institutet, has been working with dying patients. This has given him extensive experience when it comes to how people handle the existential crisis that death entails.

“We cannot escape our existential loneliness, which is based on the fact that it is impossible for us to share our innermost thoughts and feelings. Nor can we share all experiences, such as death. We have to complete the last bit of the puzzle ourselves. Existential loneliness leads to a great amount of suffering, but my experience is that it can be eased through a sense of community,” says Peter Strang.

He says that many patients with a terminal illness first become introverted with worry and anxiety when they have a short time to live. But in many cases, this then changes, and often very quickly. Suddenly, the patient is calm and peaceful.

“I usually ask what has happened, if they have had any new thoughts or something else that has had a calming effect. A common answer is that the patient has thought about an older, dead relative and how that person has felt increasingly present afterwards. Sometimes there are several relatives. The patient can see them or sense their presence very clearly, and this is a positive experience for the dying person. They describe how their relatives are there to help them.”

This phenomenon, which has been studied, is referred to as deathbed visions. According to interview surveys with palliative staff, these visions are fairly common.

“My own interpretation is that our need for community is so strong that we look for someone to share the experience of dying with. In doing so, we start thinking about those who are already gone, those who know what it is like to die,” says Peter Strang.

In 2014, he published a popular science book called Att höra till. Om ensamhet och gemenskap (To belong. A study of loneliness and community), which puts our social needs into an evolutionary context. The book argues that the security that comes from being part of a group has been such a vital advantage for survival that hundreds of thousands years ago, we developed strong mechanisms to seek out company and avoid loneliness.

Skin contact

According to this line of reasoning, the sense of wellbeing resulting from skin contact is the reward part of these mechanisms, where the pleasurable hormone rush, of oxytocin for example, encourages us to stay in a community, under the protection of the group. At the same time, anxiety connected to involuntary loneliness is described as a warning signal intended to drive us back to the group, much in the same way as pain makes us pull away a hand about to be burned by fire.

These ideas are supported by the fact that social exclusion activates the same part of the brain as physical pain does. Just over ten years ago, an American research team described an experiment in the research journal Science, where healthy subjects got to throw a ball back and forth in a virtual game, where one person, who was unaware that the experiment was fixed, became increasingly socially excluded as the others gradually stopped passing the ball to them. The test subjects were continuously monitored using fMRI, which scans the working brain, and the researchers were able to show that the social exclusion activated the same parts of the brain as that activated by physical pain.

In his work with palliative patients at the Stockholms Sjukhem hospice, Peter Strang has often seen how loneliness and physical pain go hand in hand. Peter Strang can recall many cases where patients, on their own, have suffered almost unbearable pain — pain with a high rating on the scale used by the health services. When someone keeps them company, preferably by stroking their arm reassuringly and providing skin contact, the pain can basically disappear – sometimes without any medication.

“The patients will often say that ‘right now, with you sitting here, the pain isn’t that bad, but just a moment ago it was terrible’. There is a social element, where physical pain is made worse by loneliness whilst having some company can ease it. When you understand that, you also understand that it matters how we organise the health services and society as a whole. Pain is the most common reason for seeking medical attention today, while many are experiencing involuntary loneliness. These two issues are related. I think that we could have a much healthier population if we combated the harmful effects of loneliness,” he says.

There are many investigations that show that good relationships are good for health, while bad relationships and feelings of loneliness have the opposite effect. In a meta-analysis published by the journal PLoS Medicine in 2010, American researchers compared loneliness to other known health issues, in terms of the risk of premature death. According to their analysis, involuntary loneliness is as great a risk factor for early death as smoking, and it constitutes a greater risk than both obesity and physical inactivity.

Involuntary loneliness

According to Peter Strang, long-term involuntary loneliness constitutes chronic, low-intensity stress, where the biological warning system telling you to find your group is constantly active. The long-term increase in stress hormones is the start of a process that can lead to high blood pressure and inflammation in the body, which in turn increases the risk of heart attacks, strokes and dementia. Furthermore, loneliness can mean an increased risk of depression.

“A society that wants to prevent these common diseases therefore needs to take loneliness into account as a risk factor, in addition to other lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise and smoking,” says Peter Strang.

But loneliness also appears to have a more immediate effect on the brain. In an American study from 2002, volunteer students took a rigged personality test, after which they were divided into three groups based on their supposed results.

One group was told that their personality would lead to a rich social future, another was told that unfortunately they would spend their lives in relative solitude, while a third group, the control group, were told that they were at a great risk of suffering some kind of accident. After hearing these results, the subjects got to take various cognitive tests, such as IQ tests and memory tests. The socially advantaged group did well in these tests, while the ones who believed they were threatened by loneliness had poor results — worse than the group who thought they were at risk of having an accident.

“One possible conclusion is that impending loneliness is such a shock that it has an immediate effect on our cognitive abilities and concentration. I believe we are only just starting to understand how loneliness affects us,” says Peter Strang.

But regardless of how loneliness affects us in the physical sense, it is unpleasant to feel alone. This alone is a good enough argument for wanting to combat it, according to Lena Dahlberg, docent in social work and researcher at the Aging Research Center at Karolinska Institutet. She would like to see a development where the social needs of the elderly are taken care of in the same way as their physical needs. Today, it is common to look at what everyday functions an elderly person needs help with, such as shopping, eating, showering or using the toilet. It should be just as obvious to find out which social functions need to be supported, in Lena Dahlberg's opinion.

“Feeling alone means a poorer sense of wellbeing. I'm assuming that we have an system of care for the elderly because we want them to be well looked after. If we care about the needs of our elders, then we also need to help them when their social functions fail them, in the same way that we help them when their physical functions falter,” she says.

Their life situation

Using an interview study she has closely monitored 600 elderly individuals over a period of seven years. They have answered questions about their life situation and whether they have ever been troubled by loneliness, all with the aim of identifying the risk factors for involuntary loneliness. According to the results, factors like level of education do not play a major part in this; they neither reduce nor increase the risk of loneliness. Difficulties moving entail a certain increased risk, and depression nearly triples the risk of someone feeling alone. But the most important risk factor by far is the recent loss of a spouse. In the study, there was a higher proportion of women who described themselves as lonely, something that can be almost entirely explained by more women than men having lost their life partner during the investigated period. Widowhood was, therefore, the decisive factor.

“This is important information when it comes to finding effective social measures. That has to be the next major step,” says Lena Dahlberg.

She says that there is little knowledge regarding what measures actually work when it comes to breaking social isolation and feelings of loneliness. A long line of measures have been looked at in various studies, from house calls and starting up telephone groups to providing hearing aids and connection with the Internet. However, according to Lena Dahlberg, many of these studies are flawed, for example due to the lack of a control group or a definition of what has actually been investigated: is it social loneliness, social isolation or emotional loneliness?

“Those are different things. Being socially lonely means that you sometimes lack a connection to friends and acquaintances that you feel a sense of community with, despite wanting to be a part of such contexts. Some people have few social contacts, and are happy with that, and then it is about social isolation rather than a sense of loneliness. In the case of emotional loneliness, you are missing someone to confide in on a deeper level, and this can of course happen even if you have a very large contact network. A study that only measures the number of social contacts therefore gives no indication of how lonely the participants have felt. Unfortunately, these concepts are often also mixed together in research,” says Lena Dahlberg.

As a consequence, it has been difficult to draw any conclusions from the evidence, and to show which voluntary, municipal or other measures have really been effective in terms of breaking involuntary loneliness. But some things can still be determined. For example, someone must be responsible for the project in question, whether it is a meeting point where people can have a cup of coffee, a joint cultural activity or a walk, and that person must have the appropriate training and support. The measure should also be targeted, so that one measure is aimed at, for example, widows/widowers, whilst another one is aimed at individuals who live alone and suffer from schizophrenia. Furthermore, it is good to involve the participants in the development of the activity.

A pattern of loneliness

And it is possible to break a pattern of loneliness. This is shown by the study published by Lena Dahlberg this autumn. Out of the 600 study subjects, a little over seven per cent indicated, when taking the first survey, that they often felt lonely, a number that had risen to 17 per cent when they were asked again seven years later, when the participants had reached an average age of just under 83 years. This increase can probably be explained by many having lost a spouse by this time. But while more felt lonely, about half of those who struggled with loneliness the first time the survey was taken had changed their minds the next time they were asked. Around half of them had managed to escape their loneliness.

“This is an interesting development of course. It is easy to imagine that these are people who had recently lost a spouse at the first survey, but who have then moved on after their grieving period and perhaps made new connections. We want to know what could be done to make it easier for elderly people to do this, for example by creating new contact points or meeting places, and what format these should then have. These are not questions we will find the answer to from the interviews we've already conducted,” says Lena Dahlberg.

There are also purely practical health aspects to loneliness, which are not related to how happy you are in your own company. Dermatologists have long suspected that single men have worse prognoses for skin cancer, as they often seek medical attention too late. This suspicion has now been scientifically proven, after dermatologist Hanna Eriksson conducted a study together with colleagues from the Department of Oncology-Pathology at Karolinska Institutet. The study investigated the survival rates of over 27,000 Swedish patients diagnosed with a primary melanoma sometime between 1990 and 2007. The results show that single men of all ages had a worse survival rate when it came to this disease.

“This is probably due to their illness being discovered at a more advanced stage, when the skin tumour has grown thicker. We believe this could be the result of single individuals having more trouble examining their whole body, or that they simply don’t do it at all, for various reasons. We didn’t see any differences in the initial surgical treatment once the skin change had been discovered. Older women were also diagnosed with more advanced melanomas, however, it did not affect their survival rate,” says Hanna Eriksson.

Earlier international interview studies with melanoma patients have shown that, in more than half the cases, a partner has prompted the patient to have a skin change examined, often a wife telling a husband.

“We want to achieve an increased awareness within the health services that elderly people and single men in particular could have trouble discovering their skin tumours in time,” says Hanna Eriksson.

Easing your way out of loneliness

The American social psychologist John T. Cacioppo has developed a plan, called EASE, that describes what an individual can do to break out of their loneliness.

E: Extend yourself. Initiate contact by saying hello, engage in small talk and maintain eye contact with other people.

A: Action plan. Think of some contexts where you can meet like-minded people, and seek them out, for example a choir or a club.

S: Selection. Choose the people you want to be friends with, and invest in a few personal relationships.

E: Expect the best. Assume that the people around you wish you well.

Related

Photo: Joey Guidone

Photo: Joey GuidoneSpotlight on depression treatment

Depression is very probably several different illnesses with different root causes. This may explain why current medications do not always help. Researchers are now attempting to put this complicated jigsaw puzzle together with the few pieces they have. And they are starting to see a pattern emerge.