How ketamine may help researchers find a cure for depression

The antidepressant ketamine has lead to a reawakening within the field. This according to researcher Johan Lundberg who sees new possibilities to find a cure for one of the world’s most widespread disorders.

Text: Cecilia Odlind, first published in Swedish in Medicinsk Vetenskap, No 1/2020.

Depression is one of the most common disorders in the world. But what causes this potentially life-threatening disorder?

“We don’t know”, says Johan Lundberg, Associate Professor at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet.

It is slightly odd that we know so little about an illness that afflicts about 20 per cent of all women and 10 per cent of all men at some point in their lives.

“The human brain is certainly a complicated organ that is difficult to study, but research in this field also hasn’t been prioritised historically speaking,” says Johan Lundberg.

But he also points to some complicating circumstances.

“One factor affecting research is how the illness is defined,” says Johan Lundberg.

Low and listless for more than two weeks

A common denominator in patients diagnosed with depression is that they feel very low and listless for more than two weeks in a row. But beyond that there is a large variety of sprawling symptoms, including decreased or increased appetite, having trouble sleeping or, on the contrary, having a greater need for sleep than normal. Some experience more physical symptoms such as aches or stomach problems, and others are preoccupied by thoughts and feelings of hopelessness and guilt.

“That individuals with such a variety of symptoms are made to fit under the same diagnosis is problematic. It’s likely that there are different types of disease here that may have different causes. But they’re all diagnosed as depression and when the patients are compared with people who are well, it becomes difficult to pinpoint the biological differences between the groups as the patient group is so heterogeneous,” says Johan Lundberg.

Perhaps, the heterogeneity in the patients could explain the fact that today’s first choice of medication, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), only has a positive effect on about a third of patients with depression. Another third experience some relief, and the final third are not helped at all.

“Because we don’t know what causes depression, and don’t really know how the treatment works, we are also unable to explain why it only works for some patients,” Johan Lundberg says.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may also help some patients, and sometimes it takes both. But common to both SSRIs and CBT is that it takes a long time, often several weeks, before any possible effect can be determined. And to assess the effect, it is common to test one treatment at a time. This means that the treatment is drawn out, which makes further research more difficult.

“This is the other major factor as to why getting knowledge about depression takes time. During the lengthy treatment period other external factors may affect the result, making it hard to interpret.

Fast acting effect is possible

However, in recent years a new drug has appeared that may change this. Ketamine is an anaesthetic that has proven effective against depression in low doses. A nasal spray was approved in the USA in 2019, and recently in the EU as well, for patients who have not been helped by the existing remedies. This new drug does not work for all patients either, but what is special about ketamine is that the effect, when there is one, presents itself much faster than earlier antidepressants. Many patients report feeling better within a few hours and sometimes recover after a day. The effect lasts for about 1-2 weeks, then a new dose needs to be administered.

What it is like to see such a quick recovery?

“It’s a bit hard to grasp. I’m still not used to it. But discovering that it’s actually possible to treat depression that quickly means a significant paradigm shift,” says Johan Lundberg.

But he does not believe that ketamine is the new solution for all depression.

“We don’t know enough about the long term effects. Ketamine is classified as a narcotic and suspected to be addictive, and it has a number of side effects. Studies on people who have abused ketamine in low doses as a party drug over a number of years have shown that they have impaired cognitive functions, not just compared to healthy people, but also to people abusing other drugs. The balance between risk and benefit is still unclear. Therefore, ketamine will initially only be prescribed to those who haven’t been helped by established treatments,” he says.

Johan Lundberg is enthusiastic about ketamine for other reasons, though.

“The fast acting effect enables research that could help us understand depression a lot better".

Saw clear changes

By studying patients taking the drug, researchers can systematically look for proteins involved in the recovery process. A study of 30 patients has looked at the biological changes in the brain using PET cameras, MRI scans, and blood samples. The study has not been published yet.

“But we saw clear changes in both the brain and the blood. We hope to use this to predict who may be helped by the drug but also to develop more robust models of the disease in order to find new drug targets,” he says.

The details of the inhibiting effect on depression are unknown. But it is known that ketamine works through the glutamate system, the most common signalling system in the brain. The drug has also been shown to increase synapse density in the brain, i.e. the number of nerve fibre connections in a particular area of the brain, which has been linked to recovery from depression. Last year, a study from Yale University in the USA was able, for the first time in human subjects, to link synapse sparsity in certain specific parts of the brain with the degree of depression symptoms in patients with ongoing depression. The fewer the synapses, the graver the depression was.

“Roughly you might say that when we use our brain and learn new things it changes the structure of the brain. One way of looking at depression, which entails lowered concentration and motivation as well as trouble with memory, among other things, is that the brain’s ability to learn is worsened. This is an interesting lead, while at the same time it’s known that more sparse synapses is also seen in other diseases of the brain,” says Johan Lundberg.

Not been introduced since the 1960s

Even though the exact mechanism has yet to be discovered, it is clear that ketamine uses different mechanisms than the established treatments. A drug using a completely new mechanism has not been introduced to the market since the 1960s. That in combination with the fact that the new drug proves that we’re able to fight the disease at a much quicker rate than before, has led to enthusiasm.

“There’s no longer the same sense of hopelessness within the research field, nor amongst donors and the pharmaceutical industry.

In the current ketamine study that Johan Lundberg’s led, there where only 30 patients, while interest was record-braking.

“Normally, recruiting people for scientific study is a slow process. But there have been thousands of people from different age groups and life situations contacting us about participating. Unfortunately we’ve only been able to refer them to the health care system. But the enormous interest says something about the desperation amongst the affected that feel they aren’t being helped by the current available treatments. Many suffer greatly from this disorder. That’s what gives my work meaning, to better understand depression and how to cure it,” says Johan Lundberg.

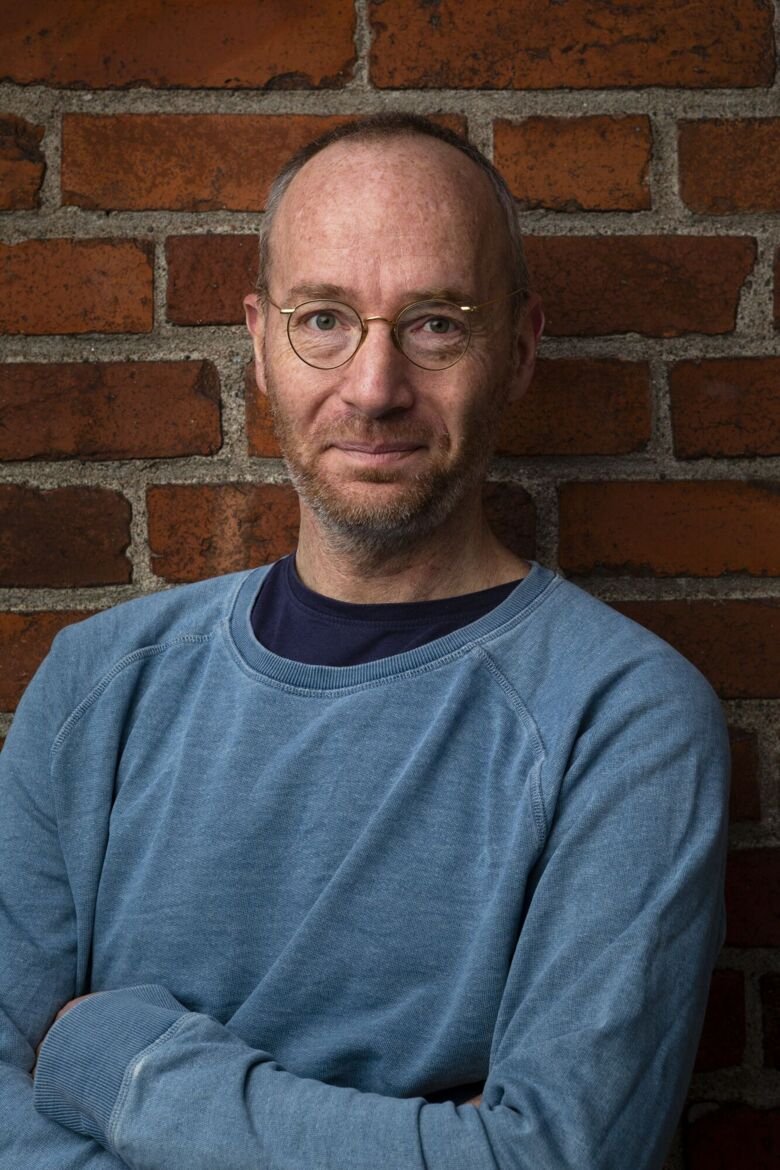

Name: Johan Lundberg

Title: Associate Professor at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, psychiatrist and head of the Section for Affective Diseases at Norra Stockholms psychiatric service.

Age: 50

Family: Married and has three children, 9, 11 and 17 years old.

Motto: You should do your best.

Role model: My brothers. They’re kind, wise and caring.

Most unexpected research finding: It was discovered fairly recently when we wanted to confirm the accuracy of a well-used PET method. It turned out, to our surprise, that the method is unreliable and partly unusable in some parts of the brain. Our finding has led to some outrage because this means that some previous research results need to be called into question.

Johan Lundberg on

... diet and depression

Of course it can have an impact. For example, a diet poor in the amino acid tryptophan, which is converted into the neurotransmitter serotonin in the intestine, can increase the risk of reoccurring depression. On the other hand, tryptophan is so common in our food that it’s difficult to “accidentally” miss it.

... exercise and depression

Physical activity clearly produces positive cognitive effects that can work preventively. However, whether it can be recommended as a treatment for depression is unclear and difficult to study. For example, it is not easy to blind such a study.

... whether depression is on the rise

There’s a lot of talk about an increase in mental illness, but whether the occurrence of depression has really changed in the last decades is still up for debate. Rather, research suggests a decrease since the middle of the last century.

... the effects of depression

The patients I meet rarely have a clear cause or time that may explain why the disease started. Rather, it sneaks up on them without them really knowing what is going on until it’s already pretty bad.

More reading

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesNew study shows how ketamine combats depression

The anaesthetic drug ketamine has been shown, in low doses, to have a rapid effect on difficult-to-treat depression. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet now report that they have identified a key target for the drug: specific serotonin receptors in the brain. Their findings, which are published in Translational Psychiatry, give hope of new, effective antidepressants.

Photo: Tom Beckman

Photo: Tom BeckmanCan psychedelics help with severe depression?

Research into psychedelic substances has taken off. Now researchers will look more closely at whether therapy together with the substance psilocybin can help with treatment-resistant depression.