Changing norms about child mothers the biggest challenge

An estimated two million girls under the age of 15 give birth every year across the globe, and the consequences can be devastating. And yet they are missing from the statistics. Researcher Anna Kågesten wants to increase girls’ opportunities and rights to decide over their own bodies.

Text: Felicia Lindberg, first published in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 4/2019.

Around two million girls aged 10-14 give birth every year, according to an estimate conducted by the World Health Organization, WHO.

“When children that young give birth, it is often the result of child marriage and sexual violence. Very few girls under the age of 15 choose to get married or have children,” says Anna Kågesten, researcher within global and sexual health at the Department of Global Public Health at Karolinska Institutet.

Her research is centred around this particular group of 10-14-year-olds, and together with local actors in the most vulnerable areas, she is working to highlight the issue and strengthen young peoples’ right to their own body.

One problem is that the youngest girls and boys are excluded from global statistics regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), as these surveys focus on individuals aged 15–49. Collecting data is often made difficult by the fact that the subject is taboo, that parents need to give permission, and that certain countries have legislation that prohibits sex before a certain age. In 2012, Anna Kågesten was part of initiating the Global Early Adolescent Study, the first study on SRHR with a focus on individuals aged 10–14.

A vital period of a child’s life

“Presenting data indicating that a need exists is the first step towards change. Our research shows that it is important to invest in this age group. It is a vital period of a child’s life as this is when behaviours, attitudes and gender norms are formed that will impact their health later in life,” she says.

When girls under the age of 15 have children, it not only affects the health and future prospects of the mother and child, it also has consequences for societal development as a whole. Girls in poor regions are the most affected, and since childbirth impacts the opportunities of getting an education and later employment, it leads to a cycle of poverty. Addtionally, daughters of teenage mothers are themselves at greater risk of becoming pregnant early, resulting in a negative spiral.

Complications related to pregnancy and childbirth are the most common cause of death among girls aged 15–19. Getting pregnant and having children is particularly risky for young girls as their reproductive organs and pelvic floor are not yet fully developed. Common birth-related complications include severe bleeding, high blood pressure, preeclampsia, infections and premature birth. Teen pregnancies are also associated with mental ill-health, social exclusion and unsafe abortions, which is particularly common in countries with strict abortion laws.

Most common in poor, rural areas

Girls younger than 15 having children is most common in western and central Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by Southeast Asia and Latin America. The estimated figures vary widely, but the incidence is generally the highest in poor, rural areas where child marriage is a common practice.

“It upsets me that the context into which we are born dictates our ability to make decisions regarding our bodies and lives. Unfortunately, many children across the world lack basic human rights,” says Anna Kågesten.

Access to contraception, safe abortions and sexuality education also varies from country to country. This also applies to norms, values, religion and legislation, factors that play a major part in how to address the issues. According to Anna Kågesten, this makes it difficult to identify general success factors.

“It is necessary for us to establish close collaborations with strong local actors in civil society. A large part of our work consists of capacity building to support local organizations to conduct their own research and interventions.”

Discussing gender norms

Anna Kågesten is involved in multiple research projects in particularly affected regions, including Kenya and Indonesia. With the help of the local organisation Ujamaa, she is investigating efforts to stop sexual violence in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, where one in four girls under the age of 18 reports that they have been raped. A highly effective six-week programme aimed at both girls and boys managed to reduce the number of rapes in this area by half in one year. A central part of the programme was discussing gender norms and how to display masculinity without the use of violence.

“I am currently conducting qualitative interviews with the participants to find out which of the tools were the most effective. We are also discussing the possibility of testing and evaluating the programme in other countries like South Sudan and South Africa,” says Anna Kågesten.

In Indonesia, she is working with the SRHR organisation Rutgers International to assess the effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality education. 10-14-year-olds’ knowledge of sex and relationships is generally very limited in the most vulnerable regions.

Start the education early

“Research shows that sexuality education generally speaking leads to a later sexual debut and less sexual risk-taking. It is important to start the education early, preferably before the age of 10, and that it is recurring and age-appropriate. Unfortunately, sexuality education is considered very taboo in certain countries, where 10-14-year-olds are considered too young for the subject. Many also incorrectly believe that more knowledge leads to more sex,” says Anna Kågesten.

She also points to established social norms as a big part of the problem. That is why it is not enough to only influence young people. Rather, a number of broad and long-term interventions aimed at different demographics such as parents, religious leaders and other influential people in society are needed.

“The biggest challenge is changing norms, but it is completely necessary to address the problem. Giving young girls better opportunities for self-determination and good health is a very urgent matter, as well as being linked to many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. But we cannot just focus on girls, we also need to bring boys and men into the work for equality.”

Strongly linked to child marriage

Statistics for girls aged 15–19 in developing countries show that 16 million girls give birth and 3.9 million undergo unsafe abortions every year.

- Statistics on SRHR for 10-14 are largely missing, including in Sweden. In the worst affected areas in western and central Africa, it is estimated that three to eight per cent of the girls in that age group give birth every year.

- 90 per cent of the children of young mothers are born into a child marriage.

- 12 million girls under the age of 18 are married off every year.

Source: WHO, UNICEF and the Guttmacher Institute.

Related reading

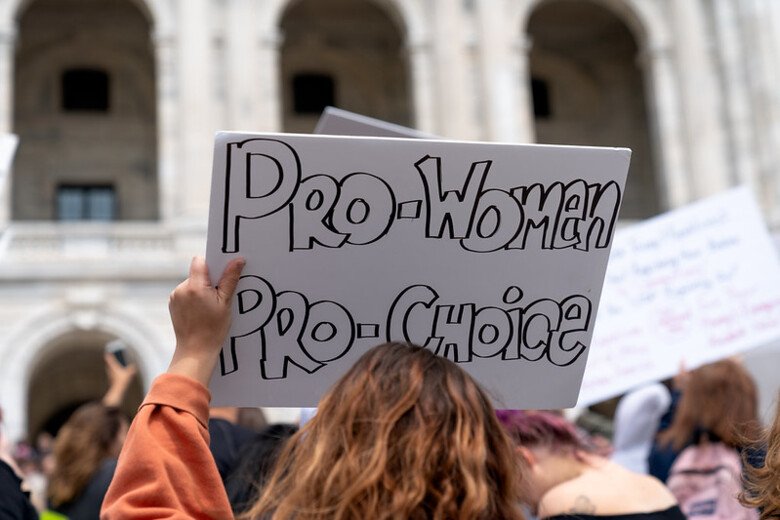

Photo: Lorie Shaull CC BY-SA

Photo: Lorie Shaull CC BY-SASafe abortion saves women’s lives

The Swedish Abortion Act came into force in 1974, giving women the right to decide for themselves whether they wanted to end a pregnancy in the first eighteen weeks. Since then, abortion procedures have become more effective, safe, accepted and accessible.