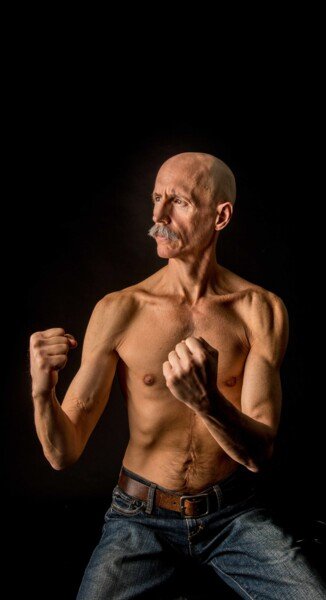

Never too late to start exercising

As we get older, the function of our muscle cells deteriorates in several ways. But there is hope. With exercise, you can also get old and tired muscle cells to shape up and perform better.

When we run to the bus or lift heavy grocery bags, we do so with the help of some of the 600 or so skeletal muscles in our body. They have an ungrateful job. Most of us do not use them enough but expect them to be there for us when we need them. It is only when the muscles start to fail us, when they ache or do not provide the power we want, that we become aware of their presence in our torso, arms and legs.

We spend even less time thinking about the muscles that work around the clock to keep us alive. The rhythmic contractions of the heart muscle continue without any wilful control on our part. This also applies to the intestinal muscle work that takes care of the food we have eaten. The respiratory muscles are controlled by signals from the respiratory centre in the medulla oblongata, but we can also consciously influence them. Each muscle group is adapted to its unique task. The contents of the rectum are kept separate from the outside world by means of a ring-shaped muscle which is constantly contracted except for when we empty our bowels. Such so-called sphincters are also found in, for example, the esophagus and the eye.

For a long time, we were only aware of the skeletal muscles. Many are found just under the skin and are easy to see and become fascinated by. In the 1800s, doctors began researching muscles to try to understand how they are controlled and what actually happens when they contract.

“For a long time, muscles were seen as fairly simple organs, but now we know that they are very complex,” says Lars Larsson, Professor of Basic and Clinical Muscle Biology at the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Karolinska Institutet.

The muscles do so much more than contract when ordered by the brain. A large part of the body’s metabolism takes place there, and the muscle cells produce a variety of proteins that are crucial for the body's functions, both locally and generally. The muscle cells are also involved in the regulation of our body temperature.

People respond differently

Muscle strength is at its greatest in a person’s 20s and 30s, and exercise can increase this significantly. However, many studies have shown that people respond differently to exercise. Endurance training pushes the body’s ability to utilise oxygen, but there are big differences in people’s ability to improve their fitness. The same applies to weight training to build muscle strength.

“We don’t know why people respond differently to exercise. It probably depends on a combination of how the body is built and its ability to respond to the signals it gets when exercising,” says Thomas Gustafsson, Professor of Clinical Physiology at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institutet.

“But if we look at a number of different effects of exercise, such as strength, fitness, balance and blood lipids, we see that all individuals respond positively in some way,” he continues.

In most people, their muscles remain fairly unchanged until they reach their 50s or 60s. After that, muscle strength decreases significantly in those who do not exercise. Large muscles such as the thigh muscles lose strength in particular. If you do not exercise into your 60s, you can easily end up in a vicious spiral. When muscle strength decreases, you become less active, which in turn causes you to become even weaker.

The ageing muscle becomes weaker due to deteriorating functions in the cell and its surroundings. Nerve impulses from the brain deteriorate and some cells lose contact completely. The genes that control the work of the mitochondria become less active, and many important proteins change so that they do not work as well.

The ageing of the muscle cells is also greatly dependent by what is happening in other parts of the body. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet are studying what is happening in the muscle cells of people who suffer from illnesses affecting the skeletal muscles. One such condition is heart failure. When the pumping of the heart is less effective, it stresses the body as it strives to maintain the blood supply in the tissues and the blood pressure. This releases substances that have a negative effect on the function of the skeletal muscles.

A large number of studies have shown that exercise is good for you in all stages of life, even if the effect drops off as you get older. Elderly people who begin weight training receive the same positive effects as younger people. During the initial stage, the transmission of nerve impulses to the muscles is improved. The muscle cells then increase their volume and allow for an increase in muscle mass. Many elderly people do not experience any dramatic increase in muscle strength, but they benefit in so many other ways.

“They learn to trust their body and use their full potential. It lets them dare to do fun things, like travel. And it can give them a richer social life,” says Thomas Gustafsson.

A biochemical process is triggered

There is currently much research being done on what happens in the muscle cell when activated. When it is reached by a nerve signal, a biochemical process is triggered where calcium is released and affects a protein complex, troponin, which in turn activates the contractile machinery. This allows the muscle cell’s smallest contracting units, the sarcomeres, to contract and create a contraction of the muscle.

By studying the calcium transport in the muscle cell, the researchers have gained deeper knowledge of what happens during beneficial exercise, and during excessive exercise resulting in overtraining. Calcium is transported via special channels out of the cells’ stores to the cell’s cytoplasm to cause a muscle contraction, and is then pumped back to the stores when the muscle is to relax.

“Normally, the channels are either open or closed. But when you have exercised, the channels begin to leak. The calcium increase in the cytoplasm stresses the cell and triggers an adaptation so that it can do its job a little better next time,” explains Håkan Westerblad, Professor of Cellular Muscle Physiology at the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Karolinska Institutet.

The increase of calcium in the cytoplasm triggers the muscle cell to start making more mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells. The cell also improves its metabolism. However, the calcium channels must not leak too much. This can happen during overtraining when the muscle has been forced to work for a long time and has not had enough time for recovery. The result is a muscle that feels weak and sluggish, and this condition can take a long time to reverse.

Research, for instance, on the calcium channels of the muscle cells indicates that food supplements with large concentrations of antioxidants can blunt positive effects of endurance training. During endurance training, there is increased production of free radicals that easily react with the cell’s proteins and is therefore potentially dangerous. The cells therefore have antioxidant systems to capture the radicals and render them harmless. Here, antioxidants such as vitamin E and vitamin C play an important role.

Moderation is key

It is easy to assume that the more antioxidants we get through food and dietary supplements, the more we help the cells stay healthy. But moderation is key. When exercising, the cells need small doses of free radicals to understand that they need to build up their capacity.

“As long as you stick to a regular diet, it’s no problem. But people who are dedicated to endurance training and at the same time buy supplements with a lot of antioxidants are just throwing their money away. In fact, high doses of antioxidants can hamper the effect of exercise,” says Håkan Westerblad.

Muscles need to be active to stay in good condition, and this is a major problem when people require intensive care. People who are sedated and totally immobile for more than ten days run the risk of complete or partial paralysis in their skeletal muscles. Some become totally paralysed and can only move their facial muscles. Although the patients can train themselves back to an optimal level, it causes great suffering. One problem is that the most important respiratory muscle, the diaphragm, often loses so much power that the patient has to train for a long time to regain the strength required to breathe independently off the respirator.

“Many patients experience a greatly reduced quality of life following intensive care, and this is mainly due to deteriorated muscle function,” says Lars Larsson.

He encountered the first patient with this condition over 20 years ago and has since been researching causes and treatment methods. Intensive care often involves the patient being completely immobile and an absence of strain or movement in the muscles. After one week of immobility, the muscle cells experience a lack of myosin, a motor protein that plays a central role in their ability to contract. In one trial, Lars Larsson and his research team provided a patient with a mechanical physiotherapist which manually exercised their ankle joint from time to time. That movement was sufficient for the activated muscle cells to retain significantly more myosin.

We now know that mechanical stimulation of the muscles, i.e. physiotherapy, counteracts muscle atrophy in intensive care patients,” says Lars Larsson.

Text: Johan Sievers, first published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskp No 1/2019.

Five things you didn’t know about...

Muscles and spinach. Since 1929, the cartoon character Popeye has claimed he gets stronger by eating spinach. And he is right! Research at Karolinska Institutet has shown that nitrate (which is present in large amounts in spinach) gives people increased levels of two proteins that are important for muscle strength. A green diet is enough to guarantee an invigorating amount of nitrate.

Muscles that twitch. Everyone has probably experienced twitching in a muscle that continues for a long time. It often happens to the eye and is more common among the young than the old. Sometimes you can get muscle twitches in an arm or a leg after exercise. The twitches are usually harmless and are due to a nerve “getting stuck in a loop”, sending a stream of signals to the muscle. The researchers do not know what causes this.

Muscles during antiquity. People have always been fascinated by muscles and how they work. The Romans thought that a flexed muscle looked like a mouse under the skin and therefore called it musculus, which became muscle in English. The ancient sculptors devoted much time to dissecting corpses and became masters of depicting muscular bodies in an anatomically correct manner.

Muscles are strong. During maximal contraction, muscle cells produce a force corresponding to 40 newtons per square centimetre. One newton is approximately equal to the weight of a small apple. A square centimetre of muscle can thus lift 40 small apples.

Minuscule muscles. The body’s smallest muscle is called the stirrup muscle, the musculus stapedius, and is located in the middle ear. It is 1-2 mm long and sits between two bones, the stirrup and the anvil. Its job is to suppress very loud sounds.